Peace through Collective Play

Highlighting the Gestural in Undermining Social Striation in the American South

Introduction

My research is centered on the idea of creating places of spatial intersection in communities that maintain relatively rigid social borders. In preparing to develop a project that meets the goal of subverting the non-social structure of rural public space, I began to evaluate the social context of Harrisonburg, Virginia – my target community, and the place where I live and work – as project site, within its macro context as a small city in the American South, and on the micro-scale of the social makeup of the city, which serves a reaching rural farming community.

It became important to me to evaluate the structuring places of intersection and exchange. There is a tendency of work in conflict transformation and peace building in social practice to follow a giver-beneficiary model. While there are times when this model may be necessary or appropriate, I found that projects of this nature enforce an existing idea of power and giving in a certain context. The question, then, became: what is my role as an outsider, and artist, in facilitating meaningful, democratic exchange between groups that are traditionally non-intersective in a shared space? Citing empathy building as a goal, I designed my work to begin the process of empathy development through the very thing that serves to develop empathy through socialization in children and young adults: play.

Because of the significance of the non-intersective habits of the American South, I decided that it was important to explore social division and intersection in a comparative study between specific, post-violent spaces and spaces of non-intersection – two challenges that threaten space, narrative, and intersectional cooperation between people of different backgrounds in the United States. In rural spaces, a lack of empathy for those with differing experiences is generally supported by a lack of urgency in the necessity of interaction between groups of differing social experience (Michelson, 2016; Denton and Gibbons, 2015). (*6)

(*6) (*2)

(*2)

Social Context Analysis of Harrisonburg, Virginia

Harrisonburg, the seat of Rockingham county, is in the Shenandoah Valley, about 30km from the Mason-Dixon divide itself, which splits West Virginia and Virginia – functional divide between social south and north, a divide created by the succession of the Confederacy during the Civil War. It is about 80km from, and demographically similar to, Charlottesville, Virginia, which in 2017 became the center for national discussions about the resurgence of fanatic nationalism after the violent “Unite the Right” rally. This event dealt with the perceived threat to white American identity by an increasingly diversifying national population, as instigated by the potential removal of a Civil War monument. The tension resultant from such a rally is present in Harrisonburg, and increasingly diverse community just northwest of Charlottesville, dealing with issues of welcome, migration, voting, and gun rights.

Notably, Harrisonburg and Rockingham county support what is overwhelmingly an agricultural and poultry-processing community. Many farming families who are generational inhabitants of the region are of white European descent. Of this population, a significant proportion are from the Mennonite community, a religious, agrarian, and pacifist community with a traditional lifestyle. Rockingham county is home to three universities, meaning more than one third of the Harrisonburg city and greater Rockingham county population is between the ages of 18 and 24 years old. As a result, a large percentage of the local social support services are directed at benefitting this demographic. A significant percentage of the population is part of the migrant community (www.census.gov/).

Fig. A: Students using double swing installed near university/city campus boundary.

Importantly, Harrisonburg was granted the status of a “welcoming city” to immigrants in 2016 on the basis of the provision of excellent social support services by local NGOs, but a legal vote to grant migrants explicit protection from arbitrary enforcement of legal status checks in 2017 was not passed by the local government. This means that while exceptional city-wide support by mostly private institutions is offered to migrants, explicit legal protection by the city is not. This continues to be representative of the meta-narrative of racial politics in the American South.

The city of Harrisonburg, and its surrounding county of Rockingham, Virginia, is a prime example of what is referred to as a community of “striated” or “non-intersective” peace (Denton and Gibbons, 2013). (*2) This term is one generated to describe suburban or rural environments that remain pseudo-peaceful, or non-violent, in theory, but this sense of social stability is fully reliant on a habit of non-interaction between unlike communities of differing social experiences. This striated peace is enforced and maintained by a lack of shared, social, public spaces for those of differing demographics. Compared to more urban environments, the existing green, social space is largely privatized, homogenizing the social experience of its users. With this in mind, I became interested in undermining the lack of public green spaces that are universally accessible in order to invite a new type of equalizing social interaction from self-selecting participants through a practice that subverts social structure on its own: shared play.

(*2) This term is one generated to describe suburban or rural environments that remain pseudo-peaceful, or non-violent, in theory, but this sense of social stability is fully reliant on a habit of non-interaction between unlike communities of differing social experiences. This striated peace is enforced and maintained by a lack of shared, social, public spaces for those of differing demographics. Compared to more urban environments, the existing green, social space is largely privatized, homogenizing the social experience of its users. With this in mind, I became interested in undermining the lack of public green spaces that are universally accessible in order to invite a new type of equalizing social interaction from self-selecting participants through a practice that subverts social structure on its own: shared play.

My project design is a direct response to the issue of this “non-intersective,” or striated, self-segregating, version of peace (Lewis, 2014.). (*5) In particular, I intended to investigate the way that people interact with one another by subverting and upholding what I will hereinafter refer to as social borders, or behavioral patterns maintained by those of homogeneous or similar social groups within a given context. In order to evaluate this, I informally mapped, through a combination of observation and quantitative research, the overarching social barrier zones in Harrisonburg and Rockingham county.

(*5) In particular, I intended to investigate the way that people interact with one another by subverting and upholding what I will hereinafter refer to as social borders, or behavioral patterns maintained by those of homogeneous or similar social groups within a given context. In order to evaluate this, I informally mapped, through a combination of observation and quantitative research, the overarching social barrier zones in Harrisonburg and Rockingham county.

I evaluated:

- Living and social spaces (apartments, community centers, parks)

- Spaces of need-meeting

- Spaces of division (transportation)

In order to strategically evaluate the city in all three of these overarching terms, I used a combination of local data, including local census and community demographic data, school census of languages spoken, mapping by dérive/observation, citing walking as an observational tool.

By doing a soft review of available of social geographic data and school census records, and through observation by interaction in various neighborhoods in the community, I identified several groups for whom interaction seemed to be lacking, including:

- University students

- English-speaking locals (city)

- English-speaking locals (farmland and surrounding rural areas)

- Non-English-speaking residents (Spanish-speaking, of varying legal status)

- Additional homogenous cultural subgroups (largely made up of those seeking asylum status)

- The Mennonite community

- Individuals experiencing homelessness (those who contribute to the social structure of the homeless subcommunity locally.)

While individuals may belong to more than one of these social groups, in general, these groups tend to self-separate. I became interested in identifying and subverting social patterns in existing shared spaces that foster limited social interactions, referred to as non-intersective spaces.

Importantly, I wanted to remove myself, as the outsider, as much as possible from the exchange itself in order to allow for equal-level participation. To mitigate the homogeneity of self-selecting participants, I became interested in finding moments of pause in existing social patterns, noting that transportation type and access are major indicators of socioeconomic status in rural areas. I found significant moments of both pause and shared, non-interactive space in waiting for the limited available public transportation, especially in bus stops that share a proximity to grocery stores, sidewalks, and importantly, parking lots.

Social Modeling for Suburban and Rural Spaces

In my initial exploration, I examined iterative making practices and patterns of co-making that are inviting. After some observation of community inclusion in my own practice of community making and arts education, it became apparent that the presence of the artist perpetuated the structure of giver (of skill, of supplies, of direction) and receiver in a way that undermined the goal of setting a circumstance of equalized exchange. The presence of the art-object-as-goal establishes a hierarchy among participants, where, if the artist is present, the artist, whether intentionally or not, remains the maker and maintainer of the circumstance (Purves 2005). (*7) This sets the artist up for circumstantial grooming in a way that felt counterproductive to democratic exchange between groups that evade intersection. I decided to focus on the existing economy of shared non-social spaces (Michelson, 2016).

(*7) This sets the artist up for circumstantial grooming in a way that felt counterproductive to democratic exchange between groups that evade intersection. I decided to focus on the existing economy of shared non-social spaces (Michelson, 2016). (*6)

(*6)

As a result, I became interested in the social structure of the playground, which acts as a reversal agent for subverting the social structure of public space. This can largely be attributed to play as a social experimentation tool and empathy-building practice space for young children. Notably, this restructuring extends to spectators (generally, caretakers) who become involved in play as peripheral participants, and interact with each other as well as those involved in the play act, undermining social borders. Because play can be independent, it became important to design or create interventions that require collaborative play-type interactions. As a result, I decided to use swings, which work with the desire to sit or rest in spaces of waiting. Because swings are not inherently collaborative in nature, I redesigned the swing so that it required – at least situationally – two people working together to function as a play item.

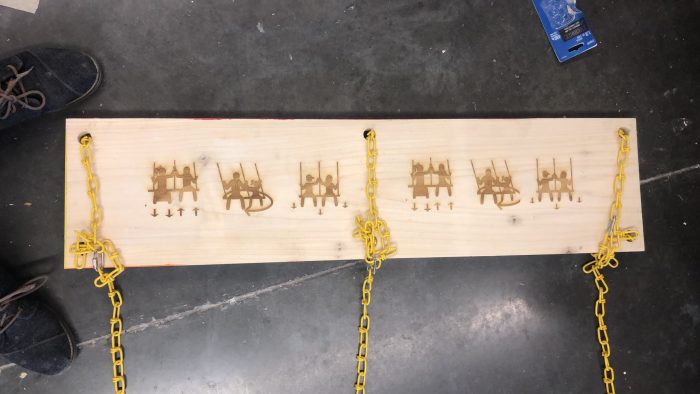

Fig. B: Participants negotiating directions on double swing for prototype.

As a result, I created two situations:

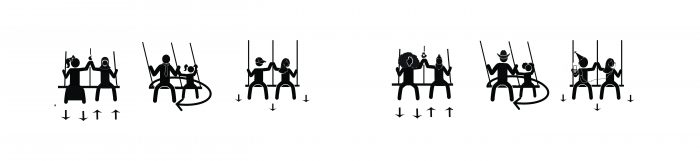

The first was a double swing (figure B), which works best with two people swinging together, either back to front, or facing in the same direction. To clarify the intention of the object, I chose to include diagrams which described, with varying intention, the uses for the swings.

I elected to have these signs mimic municipal signage, in terms of instructional pictograms, to subvert the current social rhetoric on the politics of language use in the U.S, as indicated by school registration data, because over 42 languages are spoken within the municipality of Harrisonburg (web. Harrisonburg City Schools.) (*8) according to the census of public school families. Therefore, I felt that the most inclusive option would be to rely on image-based signifiers.

(*8) according to the census of public school families. Therefore, I felt that the most inclusive option would be to rely on image-based signifiers.

Fig. C: Setting up single swings in bus shelter for interactive performance.

I made two versions of the collaborative swings: individual swings with instructions for co-use (figure D) and a double swing with instructions for use with another individual. The functional/social value of each differed slightly. The single swings, either attached together or separate, were more welcoming in some circumstances, but allowed for individual use; they are perfectly usable without a second participant, although the use of the swings, even separately, functionally re-narrates the space into a play-space, offering a solution for social interconnectedness for both the players and observing parties. Comparatively, the double swings are very difficult to use by individual people involved in play, and require a spatial ask for a second person in order to work. This creates a narrative of need and need filling, which offers an opportunity for help-based collaborative social intersection in order to accomplish play.

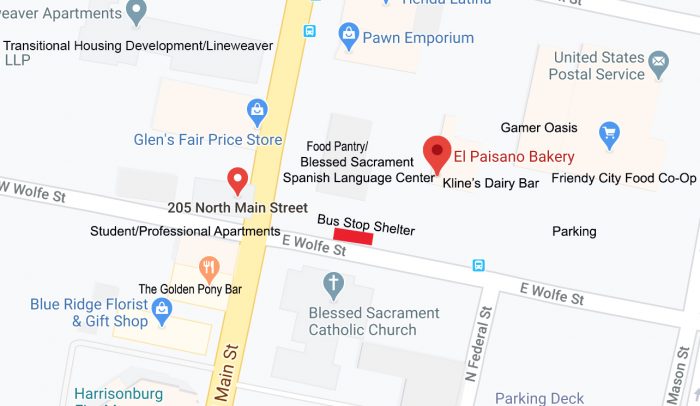

Fig. D: Sample double swing seat and instructional signage, laser-cut into swing.

Initial Trials and Prototyping

Initial trials of the swing in several identified spaces of social intersection, as described earlier described, initially focused on bus stops, with significant proximity to spaces of need meeting (grocery, clothing supply stores, municipal centers.) and pedestrian and car-based transit spaces. Figure E*1 *(1) shows the makeup of one such space, a bus-stop shelter at what I found to be a significant social boundary. This shelter is in close proximity to a parking lot, which services a Spanish-language market, a bakery, and a specialty ice cream shop that are popular with students and local families, as well as both English-speaking and Spanish-speaking places of worship, an organic, high-end local grocery store, and a food bank. Across the street are transitional apartments for those experiencing homelessness, a student bar, median-income student and professional apartments, and a confederate-flag-emblazoned variety store. This bus stop borders a popular pedestrian area as well as city parking. While an extremely diverse population shares and uses this space, there is limited, if any, social blurring; nearly all interactions between individuals are homogeneous. The swing installation here can be seen in figure E. Notably, this site is not within walking distance of any significant green spaces or parks with play space.

Fig. E: Informal mapping of social-boundary space on Wolfe Street in Harrisonburg, Virginia. Note location of bus shelter.

Early installations along social border sites, such as the one described above, have involved the installation of swings at bus stops. While engaging as objects, limited participation was accomplished for several reasons. The first is that, without a participatory-performative element, individuals were not likely to engage with the swing object absent any indication of weight support and permissible presence. While the swings themselves are all rated to carry 150+ kg, they were installed without municipal permission, and were ultimately removed before significant engagement could be achieved. Additionally, general distrust of the hanging structure limited public willingness to engage with the object.

Fig. F: Bus shelter 931, and El Paisano bakery which is located on Wolfe street in above social-boundary mapping, site for installation shown in Figure F.

Fig. G: Swing installation in bus shelter 931 on Wolfe Street in Harrisonburg, Virginia.

As a second iteration, the swings were approached as a temporary performance, installed while people used bus stops at identified social border sites, used by artists with invited participation from those occupying the space, and removed at the conclusion of the performative interaction. While only a few individuals were willing to engage openly with the object, intersective conversations about play space resulted from the installations, which came as a result of the initial use of the object-as-performance. The use of the swings by performers with the goal of engaging greatly increased, likely due to rising trust of the structure and the goals of the installation (Fig. C).

Implications, Concluding Remarks, and Plans for Project Continuation

While the work is still in progress, it has been put on hold as a result of COVID-19 and social distancing. I plan to continue to evolve the work in both performative and object-structural ways. As I continue to work with the play objects as public installations, I plan to continue to identify spaces and intersections within the community, using strategic factors such as transportation access and type, need-meeting, and utilization of public and semi-public spaces.

Since the early stages of the project, I have also partnered with an artist in Richmond, Virginia, and have done early prototype installations of swings in Mosby Court, a Richmond neighborhood that has experienced a significant increase in gun violence and person-to-person violence in the last year, to perform a comparative study in an urban environment with a known history of violence. It is our hope that, once cities reopen, and it is safe to do so, we can continue the work in Mosby Court, practicing a transfer of agency to residents by setting up a space for locals to work on making the swings with us and hanging them for themselves. This, we hope, will increase engagement by giving agency to those declaring the shared status of the spaces by hanging the swings and encouraging mutual participation with the art objects made by those who hope to use them.

Sarah Phillips ( 2020): Peace through Collective Play. Highlighting the Gestural in Undermining Social Striation in the American South. In: p/art/icipate – Kultur aktiv gestalten # 11 , https://www.p-art-icipate.net/peace-through-collective-play/