“To be silent is not neutral”: Curating collective action at The Climate Museum

Anais Reyes and Dilshanie Perera in conversation with Katharina Anzengruber and Elke Zobl

The Climate Museum in New York City is engaging in conversations around climate. By bringing the museum to the people, they aim to start a cultural shift and to empower people to action. Anais Reyes and Dilshanie Perera talk about their work at the Climate Museum, different exhibitions and actions, and the urgent need to bring the climate crisis into public and personal conversations in order to create that cultural shift. Starting dialogues and building communities that empower people to take collective action is the museum’s main goal.

Could you briefly tell us what the Climate Museum is about? Where does your individual focus lie?

Anais Reyes: The Climate Museum is the first museum in the United States focused on climate change. Our mission is to inspire action on the climate crisis with programming across the arts and sciences that deepens understanding, builds connections, and advances just solutions.

We think of our constituency as the people who are worried about climate change, but feel uncertain of what they can do about it. We know that 66% of Americans— 2 out of every 3 people—are worried about the climate, but only 6% are taking action. That includes even just speaking about climate change. So we are really working to push that leftover 60% of worried people toward active engagement. After our first few programs, we realized that every program we do has to connect people to collective actions—ones that go beyond individual consumer choices and ask people to work together to target the very social and societal structures that have caused or worsened the crisis we are in today.

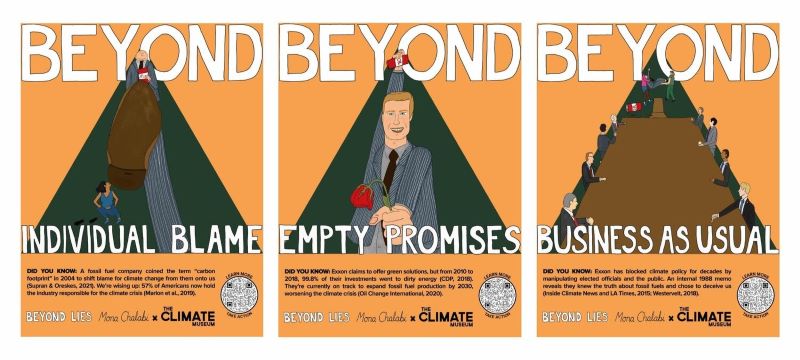

I am the Senior Exhibitions Associate at the Museum, so I do various things related to planning exhibitions—from working with artists to researching scientific concepts and data to consulting with experts across fields to planning events and talking with visitors. It’s a really great experience getting to conceptualize a whole project, see the public response, and have thoughtful conversations with our audience. For example, on July 31, we had a kick-off event for our Beyond Lies campaign. I got to talk to visitors about the history of disinformation put out by the fossil fuel industry, their role in creating the climate crisis, and what the public can do about it.

Dilshanie Perera: I’m the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Post-Doctoral Fellow in Climate and Inequality at the Climate Museum, so I am lucky to work on different kinds of programming, ranging from curatorial work to youth programs to assembling a public series of conversations that bring together climate and inequality. It is unique for a museum to critically engage both climate and inequality in its programming, and to do so through an activist lens. We think about what it means to substantively engage in social justice issues and really center those in discussions of climate. I think the Climate Museum is very unique in how we create public dialogues on climate, weaving together broader academic research and expertise from a number of fields including activism, science, journalism, community organizing, public health, policy, and beyond.

The climate topic is huge and has so many aspects. You’ve already mentioned the fossil fuel industry and the inequality issue. Do you focus on different aspects at the same time, or do you go from one issue to another organically in your work?

AR: We are purposefully expanding the conversation around climate because it allows more people to join in it. By connecting climate with inequality, fossil fuels, visual arts, poetry, politics, or other social issues, we can better connect with people’s personal experiences, interests, and values in ways that they might not have realized before. Through that, we can shift more people toward participation in and mobilization around the issue. When people think of climate change, the stereotypical imagery conjured up is distant polar bears and melting ice. That’s a very incomplete and dangerous frame through which to understand climate change. Climate is connected to the air, water, and really everything immediately around us; we need to understand and address it as such. In order to address the many geological and social impacts of climate change, we need to expand the public’s perspective of the issue, and in order for people to take action, they need to feel that emotional connection to the issue. They have to realize that they are a part of this; that we are all a part of this. Surely, climate change will affect people unequally, but it will affect everyone. That, combined with the urgency of the situation, dictates a lot of what we decide we as a museum need to talk about. Our decision to use our most recent campaign, Beyond Lies, to talk about fossil fuels and the power that they have to stall climate progress was inspired by seeing TV commercials from oil companies and being blown away by the audacity of their greenwashed messaging. In the U.S., so much money goes into fossil fuels. So much is spent keeping the industry alive even though more and more Americans, according to recent studies, consider the fossil fuel industry responsible for damages in communities and for climate change. That’s an issue that we created a program around because it was a conversation growing in climate circles, and we wanted to help continue to grow it in the public sphere and we knew we needed to highlight it.

You also mentioned the issue of inequality earlier. Could you elaborate on that a little?

DP: Beginning in January of this year, we launched a virtual discussion series called Talking Climate. It brings together interdisciplinary experts who are working in climate and thinking critically about the intersection of climate and inequality. Each month we host a conversation focused on different themes at this intersection, including grief, infrastructure, health, the law, identity, and more. We’re examining questions of long-standing historical inequalities, how they shape what we see and experience in the present, and the ways that climate affects and exacerbates those inequalities. For example, the first event we hosted was a conversation on multiple forms of climate displacement that featured the work of journalist Vann R. Newkirk, who has written about the impacts of Hurricane Katrina on the Gulf Coast, and Shavonne Smith, Environmental Director of the Shinnecock Indian Nation (located on what is currently known as Long Island, New York), who has been working on questions of managed retreat and what an entire nation does as their land is being eroded by the sea. We also discussed climate gentrification happening in Miami with Marleine Bastien, Executive Director of FANM, who is focused specifically on immigration rights and stopping the climate-caused gentrification affecting the Haitian community in Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood. Food systems were another topic of conversation: How is nutrition changing in a changing climate? How are farmworkers affected in terms of their daily experiences doing the work of agricultural labor? How is climate change creating greater heat vulnerabilities for farmworkers and how does that intersect with public health, immigration, and the law? The Talking Climate discussion series really aims to think through the nuances of climate and inequality and their effects.

AR: We also like to work with artists who address inequality through their work. For example, Mona Chalabi, the artist from our Beyond Lies poster campaign, is a data journalist and illustrator, so she uses her art as a way to explore social justice issues and recontextualize statistics that often feel distant and dehumanized. Her work looks at the intertwined systems and structures that we live in and examines their effects across society. When connected to the topic of climate, the artwork serves as an entry point into an interdisciplinary understanding of climate impacts, how we got to where we are today, and what we need to do about it.

You’ve already mentioned one format, the Talking Climate discussion series. We are very interested in how you work, and what kind of formats and spaces you create to inspire action on the climate crisis. Could you tell us something about the different programs you have—and particularly your Climate Action Leadership Program?

DP: The Climate Action Leadership Program (CALP) is focused on youth engagement and advocacy. It’s a way for us to work with high school students primarily from New York City, but also from across the United States and internationally, too. It doesn’t matter if they have a background in climate or not—students might already be organizing environmental clubs or even marches with their schools, or they might have no prior experience at all. We want to be able to empower young people so they can begin their own climate conversations or host campaigns at their schools, neighborhoods, or communities. We want to help students to see that climate change is something they can perceive all around them and take action on. The climate crisis might affect them, their families, and their communities in different ways. Being able to see themselves not only as individual actors, but really as members of various communities who can act as agents of civic engagement and raise their voices in advocacy. We have different tools that we share with students, including a project called “Climate Art for Congress,” an illustrated letter-writing campaign for students from kindergarten to twelfth grade. These students are part of a population who are not yet of voting age, but who can still communicate their passions, their experiences, their perspective on climate, and the issues that they see as most pressing in the world to their congressional representatives through this project. With the recent launch of the Beyond Lies campaign, we’ve also been able to educate young people in fossil fuel disinformation and media literacy. That’s been a big part of CALP that we’ll extend from the summer through the end of the year.

AR: Our way of working with the students helps them become more confident in talking about what they used to see as a challenging topic. That’s really what we want to do with every program that we do. With our youth programs specifically, we’re able to work with students very closely. It has the effect that these students become so ready to do whatever is required to take action on the climate crisis. I don’t want to gush about how proud we are of them, but they inspire us. They tell us that we’ve changed their lives, given them a voice and a purpose. It’s reassuring to see that version of what we do working for them and thus working for us—creating people who are civically engaged to protect the climate and ourselves.

DP: I completely agree with you, Anais—it’s really a privilege to work with young people who have both the moral clarity and the sense of urgency. The climate movement itself is led by young people—by young women of color, particularly. Being able to see all of the creative ways that they’re thinking about political engagement, climate action, and creating art that motivates action from such a young age is really incredible.

I understood your museum moves around, without having a fixed space. Could tell us a bit about this mobile aspect? You also said that you have an action room as one of the core features of your exhibition. How do you inspire action specifically in the museum?

AR: We don’t have a permanent location right now, but we focus on putting on city-wide public art projects and using pop-up spaces as we work toward scaling up. For the last few years, we’ve been grateful to have a space for interdisciplinary exhibitions on Governors Island, a cultural hub just an 8-minute ferry ride away from Manhattan. We have an old house there that we’ve transformed into our museum space with the help of the Governors Island programming team. In 2019, we hosted our Taking Action exhibition there. It was the first exhibition we did after realizing that we had to build participatory actions into every program we do. We realized that we risked talking about climate change and then people leaving our exhibitions uncertain of what they could do, or worse—feeling hopeless. We couldn’t have either of those things. We had to build momentum. This exhibition in particular connected climate, science, and society. It first took people through climate solutions currently being implemented across NYC and the globe. Then it discussed political and social barriers to progress, such as fossil fuel money in politics and the lack of climate coverage from mass media. In the final room, you could take curated actions related directly to those barriers to progress. The five actions were: (1) Talk to three people about climate change and break the cycle of silence on climate; (2) join an organization that is already doing work on climate justice; (3) sign a petition to pressure the media to make climate change a central topic in the 2020 presidential election debates; (4) call your representatives and tell them to take the No-Fossil-Fuel-Money Pledge; and (5) switch your bank to one that does not invest in the growth of the fossil fuel industry. Through the run of the show, we were really trying to figure out what people responded to, what was most effective, what was needed, what we could do in related programs, and how we can promote these actions. Ever since then, we know we have to be very strategic on how to connect people with action. It must be empowering; people have to feel they can have an impact. And they really can. In the action room of this exhibition, we offered stickers to people for each action they took and invited them to add them to a nearby wall as a symbol of their commitment. By the time the show ended, the wall was covered in thousands and thousands of stickers. The interaction created a visual representation of a shared purpose and possibility with others and exhibited the importance of seeing the impact of your actions as part of a larger movement. Through this, we were able to create a sense of motivation, direction, and togetherness, rather than leaving people to despair in doom and gloom. We think a lot about this idea of “stubborn optimism,” which was coined by Christiana Figueres, the architect of the Paris Agreement. We realize that a lot has to be done, but there are a lot of things we already know we need to do, and we just have to come together with resolve and do them.

The Climate Museum’s 2019 exhibition, Taking Action, on Governors Island. Photos by Lisa Goulet (top two), Sari Goodfriend (bottom left), and Edward Watkins (bottom right).

DP: It feels like the action room from Taking Action has informed every program that’s followed since then, and we build an action ask into all of our programs, campaigns, and events. Something else that orients our work is the “Know, Feel, Do” framework coined by the artist, designer, and theorist Sloan Leo. They asked us, “What is it that you want your audience to know? What is it that you want your audience to feel? And what is it that you want your audience to do?” This gives us three concrete pillars in planning each program to then reflect on what the most important takeaways are for our audience. The arts have the unique ability to get you to feel something emotionally and viscerally, to be really inspired. And the third piece of the framework (the “Do” of “Know-Feel-Do”) is crucial for us: what pathways can we offer people for taking action? We think of these actions specifically in terms of civic or collective actions, thus being able to think of yourself and your political engagement beyond individual consumption and highlighting the power of community and the collective. Being able to create these shifts starts by simply having a conversation. You don’t have to be an expert on climate science, you can start from right where you are or your own experience, and that’s good enough. We can build on that together.

You mentioned collaborations with artists, the role of art, and the importance of art for you. I’m thinking about the road sign series on your website. In your talk earlier this year, you also mentioned the digital action board where people could write their own messages on these signs. We’re also trying to build collaborations like that—could you tell us more about how you approach them? How do you get to know the artists and work with them in general?

One of the ten road signs installed across New York City for Climate Signals by Justin Brice Guariglia. Photo by Lisa Goulet.

AR: The project you are referring to was called Climate Signals by Justin Brice Guariglia. It had ten huge digital road signs that flashed climate-related warnings like “CLIMATE CHANGE AT WORK” and “FOSSIL FUELING INEQUALITY.” We put them up in public parks—places you wouldn’t normally see a road sign—and it was meant to stop people in their tracks and get them thinking about climate change interrupting their daily life. It was really important for us to get that project all over the city, in all kinds of demographically diverse neighborhoods. Some locations were chosen for their high traffic, while some locations were chosen because of their high vulnerability and connections to environmental injustice. Again here, there was a focus on community, on interdisciplinarity, on accessibility, on building connections to climate, on connecting personal stories, on building a better mental frame of climate—and using the art as a starting point for those dialogues. We also had an interactive exhibit at our hub on Governors Island where people could come up with their own sign messages and see them displayed alongside others’. It allowed people to insert their own voices into the artwork and become active participants in the project.

On working with the artists, I’ll say that it’s a little bit different every time with each artist, and we find them in different ways. With Beyond Lies, for example, our Design and Curatorial Associate Saskia Randle saw illustrations by Mona Chalabi in the New York Times, but sometimes we find them on social media or through personal connections. With us, the artist has space to share artwork that is an honest manifestation of their personal experience, thoughts, or artistic practice. Then it’s our job to facilitate the audience’s interaction with the works and facilitate those connections to climate action with additional programming like interactive exhibits or youth activities. Another current project, Low Relief for High Water by Gabriela Salazar, began in 2019 after seeing her artwork at a climate-themed exhibition at Storm King Art Center. Our project with Salazar, a one-day public installation and performance, was supposed to take place on the fiftieth Anniversary of Earth Day in 2020 but then was pushed back because of Covid. Now we’re planning to have it on October 10, 2021. Gabriela doesn’t consider herself a “Climate Artist” in any formal terms. She was working within her existing practice considering the vulnerability of human-made structures, and for this piece in particular, exploring themes of shared responsibility and home. On the day of the performance, we will have tables set up nearby with postcards people can fill out to contact their representatives and where people can share their written reflections on the piece and on climate change. I think that’s how we see our role as curators at the Climate Museum. The artist has their practice, and we build off of their ideas with them to create these additional opportunities to foster deeper dialogues and connect to people to direct action and to each other.

You said it’s very important to you to bring people together and to inspire action on the climate crisis. Within our work, we are continuously confronted with the question of how we can reach people who are not aware of the climate crisis, or who are not already active. Museums reach a lot of people, but there are also a lot of people who don’t go to museums. Can you tell us a bit more about the strategies you use to engage with different people to not only get them on board but to give them a voice? Do you have specific strategies, or can you give us more examples from your work?

DP: This goes back to your question on mobility, too. What was great about Climate Signals was that the museum gallery space was out in the world and people could encounter these signs in their communities, which could spark their curiosity and engagement. There’s the possibility of just coming across the art in city space as you’re walking by and having a chance to contemplate or have a meaningful conversation about it. The signs were also translated into the languages that are most commonly spoken in each of the neighborhoods they were located in, including French, Chinese, Spanish, Russian, as well as English. Being able to have these different points of access in public space was one of the aspects that informs our current campaign against fossil fuel disinformation, Beyond Lies. The series of three posters highlighting aspects of the fossil fuel industry’s decades-long tactics of deceiving the public are going up around the five boroughs of New York City thanks to our volunteers and community partners. The campaign is also extending across the U.S. and around the world, too. The conversations people initiate as they hang up these posters in their neighborhoods is a major part of the project, in addition to the artwork itself. Participating in the campaign involves sharing ideas, information, and climate stories with members of your community: friends and family, school groups, local business owners, public librarians, etc. We make resources available for volunteers to begin these climate conversations, and it’s an opportunity for members of the public to see these charismatic images, read the poster text containing some shocking facts about the fossil fuel industry’s influence on climate policy, and take action by scanning a QR code that takes the viewer to the Beyond Lies website where we have concrete ways of taking action highlighted, like calling their congressional representatives or calling the White House to make your voice heard. We’ve been thinking of the timing of this campaign and how well it ties in with the conversations going on right now in U.S. politics on climate and infrastructure. The ability to encounter these posters and the campaign out in the world, even by chance, gets the public involved. It might not always be people who are looking for climate-related pursuits but it’s even better when we can bring new people into these conversations and spark curiosity.

AR: And everyone will have a different response that we can’t predict, but there is power in all of them. Maybe someone sees the poster and they’re interested in immediately taking action. Or maybe they don’t call their representatives, or they don’t take the actions, but they’re starting to think about climate in relation to their neighborhood and maybe they’ll bring it up to a friend or post on social media. Over time, as climate becomes more of a familiar topic, people will start to see it as something they can talk about and engage in more passionately or at least unabashedly. And that’s a different kind of power that we must recognize we have as a museum. For example, going back to the high schoolers in CALP—they’re super interested in climate and taking action, and even though they are still learning, they are also sharing their work at the Climate Museum with their parents, friends, and grandparents. Not every grandparent will call their representative, but now they know someone who is taking action and they will also tell others about it. That escalation builds up and spreads out over time. Eventually we hope that we’ll get to a place where our entire culture has had this revelation that climate and sustainability must be a constant focus built into everything we do—that things must be done differently than they are now. Rather than just working toward the accumulation of climate-friendly actions, it really is pushing us toward a major cultural shift.

You mentioned the importance of public space in bringing about a cultural shift, but what about the digital space? We’ve had our own difficulties in implementing the digital space in our work. How do you use digital platforms such as Instagram or your blog? How significant is digital space for you?

DP: Digital space is very significant, and it’s something we’ve had to get creative with during Covid as well. In a very short time, we had to understand how to engage the public and how to continue programming through different digital platforms. For example, what does it mean to host an event in online space, like we do with the Talking Climate discussion series? How can we pace the events, encourage interaction, and foster a sense of openness that prepares them for a conversation or event? With Talking Climate, one answer to this question was to begin each panel discussion with a poetry reading to offer an emotionally resonant opening into the conversation. We’ve found that this works wonderfully.

One of the things that surprised me initially was that people were tuning into our online events from all around the world. That got us thinking about the different kinds of improved access that’s possible through online space, whether it’s because we can reach across time zones and continents, or because we can include accessibility features like asynchronous viewing, closed captions, and sign language interpretation. This learning is something we want to carry into future programming. We want to create something that feels really special that people can access, join in, and share with others. We have the full archive of the events that we’ve hosted over the past year and a half on our YouTube page. This is part of an ongoing conversation at the museum: How do we extend all the lessons learned over the past 18 months online into the next phase of our programming?

AR: There’s a back and forth: what did we learn from in-person programming to inform the digital space and what did we learn from online programming to inform our physical spaces? It’s all centered around building a sense of community. We also have a very active comment section when we livestream panel discussions to YouTube. We start by asking people where they are watching from or what questions they have for the speakers, but we’ll also insert questions just for the audience members, such as “What do you think about x? How do you feel in response to y?” We work very purposefully to create welcoming spaces, even though it is digital.

Our project is called “Spaces of Cultural Democracy.” You mentioned the cultural shift and civic engagement that’s all part of how we want to shape and live the concept of democracy. What is cultural democracy for you? Do you work with this term?

AR: This term reminds me of the idea that museums should remain neutral, apolitical spaces— that not talking about things like climate change and justice maintains museum neutrality or preserves formality and authority. Museums are turning away from that more and more, but it’s still a question many face. We consider ourselves an activist museum not just because we connect people to action, but because we see it as our civic duty as a public institution to use our platform, our knowledge, and our access to experts toward social betterment. We must employ that public trust toward justice for the communities we serve. It’s a question of integrity. To be silent is not neutral. Remaining neutral only serves to preserve the status quo—and as we all know, that isn’t working anymore. I think because we’re a smaller and newer museum, we have a lot of space to decide for ourselves what needs to be said, how we want to say it, and how we facilitate those dialogues. As we’ve said, we aim to be accessible, to uplift diverse voices, and welcome all perspectives from wherever they are coming from. We believe that civic engagement, activism, and cultural growth are all part of the same infinite loop propelling people towards a just cultural democracy. Everything we do is in an effort to show our visitors how culture and democracy are tied together and how they have a valuable role in that.

DP: It’s an honor to participate in this conversation about cultural democracy, this new field that you all are building and theorizing. It makes me think of one of our advisors, Edward Maibach, who is the Director of the George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communications and an expert on climate communications and public health. One of the things he says about contributing to the cultural shift on climate is having consistent messages delivered by trusted sources and repeated often. We’re really taking that to heart, especially because museums enjoy a high level of public trust. Because of this, we have a responsibility to our audiences. Being a cultural institution and having people look to us for particular kinds of information, leadership, or programming resources gives us a platform for creating consistent messages about taking action—working to transform people’s understanding of the self, the collective, belonging to larger systems of democratic engagement, and thinking deeply about what justice can look like in practice. It’s fantastic for us to have this new term to think with, too.

Interviewed on August 4, 2021

Dilshanie Perera, Anais Reyes, Katharina Anzengruber, Elke Zobl ( 2021): “To be silent is not neutral”: Curating collective action at The Climate Museum. Anais Reyes and Dilshanie Perera in conversation with Katharina Anzengruber and Elke Zobl. In: p/art/icipate – Kultur aktiv gestalten # 12 , https://www.p-art-icipate.net/to-be-silent-is-not-neutral-curating-collective-action-at-the-climate-museum/

Artikel drucken

Artikel drucken Literaturverzeichnis

Literaturverzeichnis