Audience Development

Getting people from very different social backgrounds involved in the arts

Introduction

“Audience development means creating a love affair between arts and audiences”, according to the leader of the education department of Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. The education department was installed by Sir Simon Rattle, the chief conductor of the most famous German orchestra, who himself comes from the UK, where “audience development” was invented. Rattle installed the first department for education and audience development in a German classical orchestra in 1995. For a German orchestra, educational work and the search for new, unusual audiences was a kind of revolution – and it took Rattle a lot of effort to convince everyone to take part in these educational activities. Since then, the Philharmonic has produced, often in cooperation with choreographers like Roysdan Maldoom, several dance and music projects, mainly with schoolchildren from some of the more deprived areas of Berlin. And since then, arts education and audience development have been pursued in other arts institutions all over Germany.

What’s new about Audience Development?

Audience development is an active process of connecting new audience groups to an arts institution. Audience development works with ideas and strategies from cultural education as well as with marketing strategies. It develops new approaches to marketing and promotion, different ways of developing, curating and distributing the arts, and new educational ways to communicate ideas, content and aesthetics with different target groups.

1. Why some people attend arts events and others avoid them

The first step in any audience development project is, of course, to have knowledge about potential audiences. Why do you personally attend arts events? Why do you visit a museum, or go to the theatre or concert? Is it because you are particularly interested in a specific aesthetic or topic? Or is it because you like the location? Or because you want to go out with friends, using the concert as a starting place for a nice evening out? Is it because the museum visit fits well with your Sunday afternoon walk? Is it because the classical concert is associated with picnicking in the park? Is it because you were invited to an opening and expect to meet nice and interesting people there?

If you want to know which kinds of positive incentives you have to develop to motivate people to attend arts events and become involved in the arts, you have to first find out why some people like to take part in the arts, and what prevents other people from engaging with the arts.

Motivations for arts attendance

Existing audience research shows the following motivations:

- Social interaction: to experience something special with a partner or friends

- Entertainment and distraction

- To experience something beautiful and out of the ordinary; stimulation

- Novelty: to experience and learn something new

- To be informed

- To pursue and demonstrate a certain lifestyle

It is important to distinguish between motivations that are prompted by social desirability and those motivations that spring from an inner need. Despite the fact that the majority of respondents rank „entertainment“ at the top of their own personal motivations, they also generally stress the „educational value“ of the arts for society as a whole (see Mandel 2005; 8. Kulturbarometer) (* 1 ). In our own empirical studies, which were conducted at Hildesheim University in 2005, we found that the need to socialise through arts events is more important to most arts attendees than the need to learn something new. And it is important to bear in mind that the personal motivations of most non-professional arts attendees are different from those of arts producers and art policymakers. Producers of art and culture tend to presume an intrinsic interest in the aesthetics and content of the arts. Cultural policymakers highlight the educational value for the population, whereas the individual arts attendee greatly appreciates the social dimension of an art event: going out with a partner and friends to see something beautiful, or just to have fun.

(* 1 ). In our own empirical studies, which were conducted at Hildesheim University in 2005, we found that the need to socialise through arts events is more important to most arts attendees than the need to learn something new. And it is important to bear in mind that the personal motivations of most non-professional arts attendees are different from those of arts producers and art policymakers. Producers of art and culture tend to presume an intrinsic interest in the aesthetics and content of the arts. Cultural policymakers highlight the educational value for the population, whereas the individual arts attendee greatly appreciates the social dimension of an art event: going out with a partner and friends to see something beautiful, or just to have fun.

Let us move on to the opposite.

Barriers to arts attendance

According to numerous surveys of both visitors and non-visitors, attending arts events is generally limited to those segments of the population with a high level of education. People with lower levels of education do not normally visit the publicly funded arts institutions in Germany. If you ask them why they do not attend arts events, they will first tell you that it is too expensive, or that they do not have enough time. Hardly anyone answered that the arts are boring or irrelevant; this is because the majority of the population in Germany generally have a positive image of high art culture. Only if you ask them more indirectly can you find out more about their true reasons. We conducted a study on the barriers faced by non-attendees (Mandel/Renz 2010) (* 3) and found that most barriers have much more to do with social and psychological reasons:

(* 3) and found that most barriers have much more to do with social and psychological reasons:

- Financial reasons

- Lack of time

- Assumption that the arts are boring

- Fear that the arts are more like work than leisure; fear of not understanding the arts due to the lack of an adequate education

- Assumption that the arts do not fit in with one’s own lifestyle (none of their friends and acquaintances are arts attendees); fear of not knowing the etiquette

- Assumption that the arts have nothing to do with one’s own life

The national image of arts and culture within the German population

While conducting empirical research on the motivations and barriers to arts attendance, I found that, independent from the age, social context and other similarities between visitors and non-visitors, there are certain images and attitudes towards culture and arts which seem to be the same all over Germany. These images and attitudes influence the funding policies, presentation and consumption of the arts. As can be seen in numerous studies of arts attendees, for the vast majority of Germans, “culture” is primarily understood to refer to the traditional high art forms, like classical drama, literature and fine art. Other meanings of culture, such as “everyday culture“, „popular culture“ or „the culture of the nations“, are identified much less frequently. The respondents’ own cultural activities and preferences are not perceived as “cultural”. Findings from interviews with students from Germany compared with those from other countries support the assumption that the image of culture is conditioned nationally. Foreign students from other countries tend to have a meaning of culture that encompasses much more „everyday life culture“ than the Germans have.

90% of the German population think that culture is of high importance for society, and even the majority of the non-attendees (60%) think that culture and the arts are very important and should be subsidised even more than they currently are. Although the vast majority of the German population has a very positive attitude and image of culture, and although we in Germany spend nearly 10 billion Euros of public money each year subsidising the arts – more than any other country in the world, apart from Finland – only 8% of our population regularly attends the publicly funded arts institutions in Germany. Of those who do visit arts institutions, nearly all have a high level of education.

“Culture and art is a good and valuable thing but it has got nothing to do with my life” – this quote from a typical non-attendee is, in short, the main finding of our studies. The image of the arts as something very special, far removed from one’s own activities, the perception that the arts are exclusive and elitist is a hindrance for people to partake in arts events. This image of the arts is reinforced by cultural policy and arts institutions in Germany. In Germany we have the tradition of promoting and publicly funding mainly high-art forms. Culture still is an important distinguishing factor, as was demonstrated impressively in Pierre Bourdieu’s studies from the 1970s (compare Bourdieu 1970) (* 2 ). High art culture is still reserved for well-educated people. Gerhard Schulze’s empirical studies reveal that arts participation is an important factor in realising certain lifestyles and that the way of participating in and interacting with the arts depends crucially on one’s own social standing.

(* 2 ). High art culture is still reserved for well-educated people. Gerhard Schulze’s empirical studies reveal that arts participation is an important factor in realising certain lifestyles and that the way of participating in and interacting with the arts depends crucially on one’s own social standing.

Which factors inform the Germans’ image of culture?

It is the traditions of a country in relation to culture and the arts that are most responsible for that country’s perceptions of culture and the way it deals with culture. In Germany, the Classical Age of the 18th Century – the age of Goethe and Schiller – is considered to be the height of German culture. The perceptions of the arts and culture as a timeless value of the „good, true and aesthetic“, in contrast to politics and everyday life, shape the perception of culture in Germany to this day. Culture in those times became the privilege of the educated classes, as opposed to the pomp and spectacle of the aristocracy and the popular „people’s culture“ of the simple working classes. The typically German distinction between serious „E“ culture and popular „U“ culture developed during this time.

After the Second World War, policymakers in Germany continued to promote serious „high“ culture as the valuable culture and developed their arts funding policies accordingly. This image of culture is still being promoted today – and still today, only a small, highly educated elite of the German population could be considered regular arts consumers.

Initiatives of the New Cultural Policy, established in Germany in the 1970s (see Hoffmann 1979) (* 4 ) to promote other socio-cultural forms, were only of marginal influence and did not manage to change the predominant idea of culture. 85% of public arts spending goes into high art institutions, while only 5% goes into third-sector multicultural, interdisciplinary institutions or into cultural education programmes. Guarantying the freedom of the arts is the most important criteria for cultural policy; moreover, it is the only criteria concerning the arts which you can find in German law (Grundgesetz, Art. 5, Abs. 3). There is hardly any money for audience development activities and cultural education in Germany, as audiences were not considered to be important until recently. As most arts institutions were public institutions or highly subsidised, it mattered little whether they were popular amongst the population or not, or whether they managed to reach their intended audiences or not. Preserving the freedom of the arts and keeping them isolated from political and social needs is still the most important criteria of cultural policy.

(* 4 ) to promote other socio-cultural forms, were only of marginal influence and did not manage to change the predominant idea of culture. 85% of public arts spending goes into high art institutions, while only 5% goes into third-sector multicultural, interdisciplinary institutions or into cultural education programmes. Guarantying the freedom of the arts is the most important criteria for cultural policy; moreover, it is the only criteria concerning the arts which you can find in German law (Grundgesetz, Art. 5, Abs. 3). There is hardly any money for audience development activities and cultural education in Germany, as audiences were not considered to be important until recently. As most arts institutions were public institutions or highly subsidised, it mattered little whether they were popular amongst the population or not, or whether they managed to reach their intended audiences or not. Preserving the freedom of the arts and keeping them isolated from political and social needs is still the most important criteria of cultural policy.

2. Cultural participation as a goal of cultural policy

Cultural policy in favour of the audience – the UK model

At the other extreme in terms of the meaning of the arts within society and the efforts in favour of the audience is the UK. There, the arts are considered less as a value in themselves, like in Germany, but as an important contributor to the development of society and as a key economic factor. “We believe that the arts have the power to transform lives and communities, and to create opportunities for people throughout the country. We will argue that being involved with the arts can have a lasting effect on many aspects of people’s lives. This is not just true for individuals, but also for neighbourhoods, communities, regions and entire generations, whose sense of identity and purpose can be changed through art” (www.artscouncil.org.uk).

The UK Department for Culture, Media and Sports set the official goal to “broaden access for all to a rich and varied cultural life”, to “develop the educational potential of the nation’s cultural resources, raise standards of cultural education and training”, to “ensure that everyone has the opportunity to develop talent in the area of culture”, and to “promote the role of culture in combating social exclusion” (Council of Europe 2002) (* 5 ).

(* 5 ).

Money is only given to those arts institutions that have proven efforts in developing audiences. In contrast to Germany, policymakers in countries like the UK, the Netherlands and Sweden have shifted the focus from funding arts production to funding arts participation.

3. Audience Development programmes in the UK

The UK was the first country in Europe to set up a national programme for audience development. It was set up by the Arts Council as a five-year programme of action research from 1998 to 2003, with the goal of encouraging as many people as possible from all backgrounds to participate in and benefit from the arts. The Arts Council invested £20 million in the programme, which sought both to reach more people and to develop an audience that is more representative of society as a whole. Arts and cultural institutions could apply with innovative best-practise models for reaching new audiences for their institution. The groups that were selected received money from the Arts Council to develop, implement and evaluate their projects.

The main target groups of the audience development programme were general audiences, young people, families, ethnic minorities (diversity), socially deprived groups (inclusion), rural populations, and older people. Some examples of selected programmes include:

- Collaborations with popular TV channels, which were most successful in reaching general audiences

- The first “Bollywood” drive-in cinema, initiated by the British film institute for migrant families from South Asia

- Young people were reached through SMS text messaging and arts institutions went into night clubs

- Some of the chosen projects experimented with new times and places, like theatre events at lunch time, poems on the underground

- Creative writing projects took place in hospitals, and classical concerts in job centres; artists worked with people in rural areas and produced a film with them

One of the main findings of the programme was that it is possible to reach all kinds of people for the arts if you find the right ways of presenting the arts and approaching people: “We believe not in changing audience behaviour but much more in challenging and changing the way art is developed, presented and funded” (Von Harrach, Viola in: Mandel, Kulturvermittlung. Zwischen kultureller Bildung und Kulturmarketing, Bielefeld 2005). The other main finding is that acting in sync with the needs of an audience does not mean a decline in artistic quality, as is often feared by artists in countries like Germany. “One of the most compelling conclusions of the programme is that organisations that understand, trust and value their audiences are more likely to produce powerful art and therefore more likely to thrive” (Peter Hewitt, Chief Executive, Arts Council England, in: New Audiences for the Arts, London 2004).

4. How does audience development work?

Methods of Audience Development:

- Research

- Marketing: product policy, price policy, distribution policy, service policy, communication

- Arts education

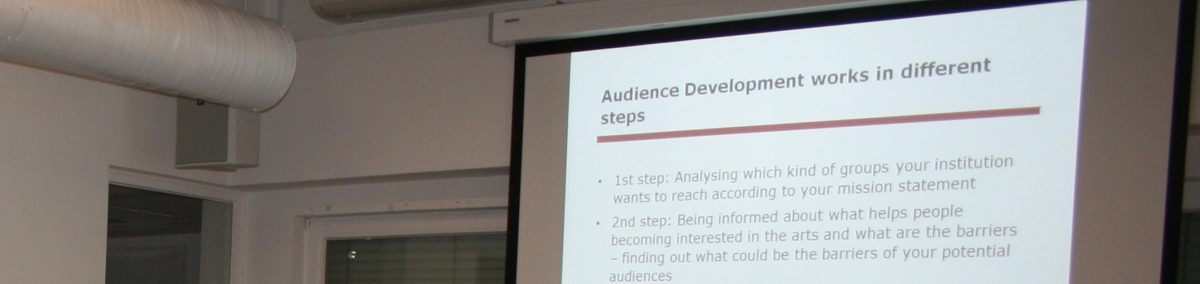

Audience development works in four different steps:

- 1st step: Analysing which kinds of groups in the population your institution wants to reach according to your mission statement.

- 2nd step: Becoming informed about the general reasons why certain groups of people attend arts events and others do not, what helps people become interested in the arts and what are the barriers – finding out the barriers your potential audiences face. Finding out the potential connections between the arts programmes your institution offers and people’s needs and actual interests. What are the attractive and popular aspects of your programme?

- 3rd step: Inventing measures and methods to present and communicate the programmes of your institution in a way that is attractive to your target groups.

- 4th step: Finding ways of connecting and bonding with first-time attendees to your institution; building long-term relationships and making them become regular attendees.

Examples of Audience Development

Tate Modern and Homebase: Everyday objects specially designed by famous artists, such as garden pitchforks, were sold in big department stores (a collaboration of Homebase stores and the Tate Gallery). Everyone who bought one of the objects also received a ticket for the Tate Modern. The goal was to make people interested in the artworks presented at the Tate Gallery.

Cesar at HAU: The avant-garde theatre Hebbel am Ufer, situated in Berlin Kreuzberg, a part of Berlin with a high number of Turkish immigrants, invited the rap music star Cesar, who is very well known amongst Turkish young people, into their theatre. The goal was to get these young Turkish people from the neighbourhood, who normally would never go into public arts institutions, into the theatre and show them that it is also their place; to give them a feeling of belonging there and to change their image of the theatre as a boring place.

“Give each pupil at primary school a musical instrument and teach them how to play it”: When the Ruhr area in Germany became the 2010 European Cultural Capital, the German cultural foundation decided not to give money for an arts festival as part of the cultural program, but to give money to all of the primary schools of the region to pay music teachers and buy musical instruments so that every pupil, regardless of his family background, could learn an instrument. The goal was to start with arts education in early life to give people the competence to get involved in the arts and to take advantage of the arts in their personal lives.

As these examples show, the goals of audience development programmes can be very different.

5. Which general strategies can help to build a closer relationship with your audiences?

It is important to remove barriers to attendance through popular ways of presentation and by addressing the perceived lack of knowledge. I would suggest five main general strategies to ease access to the arts for more people:

1. Service strategy

Provide pleasant general conditions for arts attendance that cater to the different needs of people, including a café, friendly and knowledgeable staff members, and easy-to-use booking systems. All these are basic requirements in order to make potential visitors feel welcome and appreciated.

2. Event strategy

The enormous popularity of special events among all segments of the population (see Zentrum für Kulturforschung 2005) reflects the need for communicative cultural experiences. Special events encompass arts programmes set at unusual times and in unusual places which consider the need for socialising and entertainment. Unlike normal arts programmes, an event setting allows people to communicate with one another, to eat and drink, and to be actively involved with all senses. Moreover, special arts events will attract much more interest from the mass media and the general public than the „business as usual“ of arts producers. Such events also ease access. Events, professionally designed and aimed specifically at creating new attention for special groups of the population, can have a lasting effect on motivating more people to participate in the arts.

3. Outreach strategy

Visitors’ surveys show that certain groups of non-attendees can only be reached if arts institutions leave their houses and perform in the everyday surroundings of those groups. Artists should go into schools and kindergartens; artistic and cultural performances could take place at school parties and community meetings, in discotheques or even in supermarkets. It can be very exciting and fruitful for both sides to bring together avant-garde arts with amateur art and with the everyday lives of people.

Another successful way of reaching certain groups involves collaborations with mediators and multipliers or the arts ambassador model, where you work with multipliers from difficult-to-reach groups and ask them to make the first contacts on your behalf.

4. Mediation strategy

As there is such a strong correlation between arts participation and interest with the level of education, less educated segments of the population need to be addressed and mobilised very specifically – if possible at an early age, through kindergartens and schools, which are the only institutions with structures enabling equal opportunity access to the arts.

Arts and culture are not self-explanatory. The lack of education is one of the largest barriers to participation in cultural activities. Here a diverse portfolio of educational activities needs to be developed, which link to the respective target group’s background, interests and perceptions. Arts mediation should start with adequate arts PR that avoids typical arts jargon and speaks the people’s language. And it should continue with lectures, seminars, and workshops specially designed for different target groups. Another important factor in getting people involved with the arts is to get them out of the passive role of spectators and let them actively take part in the arts.

5. Relationship strategy

The feeling that an arts organisation and its programmes are relevant to one’s own life, and that one „belongs“ to it, is the basis for a lasting relationship and the conversion from occasional to regular attendance. On the one hand, people are less and less willing to be „tied“ to a certain institution, as is reflected, for example, in the declining number of theatre subscriptions in Germany; on the other hand, arts institutions’ membership programmes and friends’ associations are booming. Such membership schemes can deliver not only exclusive benefits, like much-appreciated direct contact with artists, but also further the relationship with a special group and the feeling of a shared responsibility for the success of a cultural institution.

To be successful in audience development it is necessary to involve not only the marketing and education departments, but every member of the institution. Audience development means a whole new way of thinking: it means considering the (potential) audience as an integral part of the institution and thinking about their needs and interests from the very beginning when planning new programs. It means becoming people-focused and curious about the audience.

6. Program Strategy

One of the main findings of a research project on inter-cultural audience development in public arts institutions (Mandel 2013) was that institutions can only reach a new, diverse audience, different from the typical art user milieu, if the institutions change their programming. Only if the programme, the content and the aesthetic is relevant and attractive to the groups an institution wants to reach will it be possible to attract them and, moreover, keep them as audience members. The best way of producing relevant programmes without losing one’s own artistic quality and mission is to invite members of these new audience groups to actively participate in a common cultural project and thus become co-producers.

7. Institutional change management strategy

In order to set up new strategies of communicating, presenting and producing with respect to new audiences, arts institutions need to adapt their mission and organisational structures. Teamwork and a less hierarchical leadership style are important for successful audience development that involves not only the marketing and education departments, but every member of the institution. Audience development means a whole new way of thinking, one that considers the (potential) audience as an integral part of the institution, respects their needs and interests, involves their ideas in planning new programmes and makes them an active part of the institution. For publicly financed arts institutions, the process of audience development could be a chance to develop the organisation from an elite niche into a meaningful and important space for a diverse population.

Birgit Mandel ( 2013): Audience Development. Getting people from very different social backgrounds involved in the arts. In: p/art/icipate – Kultur aktiv gestalten # 03 , https://www.p-art-icipate.net/audience-development-getting-people-from-very-different-social-backgrounds-involved-in-the-arts/

Artikel drucken

Artikel drucken