Zines, Art Activism and the Female Body: What We Learn from Riot Grrrls

In 1973, the United States Supreme Court heard Roe versus Wade case and ruled that abortion was a woman’s legal right in the United States.*1 *(1) Yet, each state has the ability to enact their own abortion laws and interpretation of The Constitution. 2019 has seen multiple states make abortions illegal after six weeks, with possible prison time for both providers and women.*2 *(2) In 2006, Tarana Burke started the #MeToo movement, calling women of color, sexual assault and violence survivors to take a stand with the goal of promoting “empowerment through empathy.”*3 *(3) In 2017 the #MeToo movement received global recognition when American celebrities started to use the hashtag in response to Harvey Weinstein and other experiences of sexual assault and harassment in Hollywood.

As we watch women’s bodies being attacked and reproductive rights decided by politicians, women in the United States and around the world are standing up and fighting against the laws that are being created to determine what a woman can and cannot do in their lives and with their bodies. Yet, with all the attacks on women, art activism is an important site of resistance, especially surrounding women’s reproductive rights and body politics. Exploring art activism as a feminist act is central for understanding resistance to body policing. There are various examples of current art activists around feminist body politics, but often we forget about the long history of women as political and social activists, especially young women activists.

The discussion of body politics, especially around women’s sexual and reproductive rights, has occurred in many activist forms throughout the feminist history of the United States. Although there are important discussions around women’s rights and body politics all over the world, I want to focus on the history of American art activism, especially as it is situated in punk music subcultures. Specifically, the riot grrrls of the 1990s, who started in the United States, and their use of zines as tools for feminist art activism. I will start by discussing a short history of feminist reproductive rights and body politics activists in the United States and then address how punk feminists used the art of zin-ing to present ways in which young women could confront sexual violence and reproductive rights through the use of women’s self-defense and narratives. By focusing on these young feminist activists and their art activism, I will present one way that feminist art activism was used for education and empowerment and social change.

A Brief History of Abortion Rights and Body Politics in the United States

At the same time as the Roe v. Wade decision was being made, anti-sexual violence activism started in the United States. Support structures for survivors, new laws, and advocacy groups were becoming visible. Moreover, the first rape crisis centers were established in the early 1970s by women who did not feel the law was meeting the needs of sexual assault survivors. It was in 1975 that Michigan passed the first rape shield law, protecting victims from having their sexual histories used in court.*4 *(4) In 1978, the US Congress passed a rape shield law as well. In 1994, the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) was passed by the U.S. government, making sexual violence a violation of an individual’s civil rights. In 2001, April was declared to be “Sexual Assault Awareness Month” in the United States, hoping to bring more awareness to sexual assault and sexual violence. Yet, it wasn’t until 1993 that marital rape was a crime in all 50 states.*5 *(5) Within the United States, recently, the #MeToo Movement and the call for public figures such as Matt Lauer or Harvey Weinstein to be removed from their positions of power present the growing number of protests and sexual violence awareness throughout the United States.

The history of reproductive freedom in the United States is extensive. Activists such as Margaret Sanger and Emma Goldman led the fight for access to birth control, sexual freedom and advocacy, as well as women’s rights to control their own bodies and reproductive health. Prior to the 1973 Supreme Court decision, in the United States abortions were controlled through state laws and were not considered a federal matter. The first abortion law was passed in the 1820s, limiting abortions after four months. By the 1900s, the American Medical Association (AMA) advocated abortion laws in most states. The AMA’s involvement occurred in order to stop midwives and home remedies that were being used to perform abortions. As women, midwives were taking power and control away from medical “regular” professionals and giving women power over their bodies and reproductive choices. They were seen as unwanted health care providers by the largely male medical profession.

It was primarily the advent of the medical profession in the United States and the establishment of the AMA in 1847 that pushed doctors to be strong lobbyists against anyone who they considered “irregular” (Baehr, 1990). (*2) Doctors wanted more control over abortions, therefor having more control over the medical profession on a larger level. It was the focus of male doctors to convince male politicians and middle-class public that controlling women’s bodies and reproductive choices was important to maintain social order (Baehr, 1990, p.2).

(*2) Doctors wanted more control over abortions, therefor having more control over the medical profession on a larger level. It was the focus of male doctors to convince male politicians and middle-class public that controlling women’s bodies and reproductive choices was important to maintain social order (Baehr, 1990, p.2). (*2)

(*2)

The connection between the anti-abortion movement and the church has a relatively short history. It was not until 1869 that Pope Pius IX said abortion was wrong. Prior to this point, the relationship between the Catholic Church and abortion was a bit different. During the 1960s and 1970s, churches often became activists for the abortion rights movement. Among other examples, New York City clergy founded the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion (CCS), an international group that assisted women in obtaining abortions—whether legal or illegal.*6 *(6)

Prior to the 1970s, The Rape Narrative as told in the United States was one of a young woman, alone at night, without a man to protect her. Attacked by an unknown assailant, she fails to protect herself. Usually, the woman is middle or upper class and white, while the attacker is black, making the narrative racially problematic and adding to longstanding cultural racism (Anderson, 2005). Poor women, women of color, and sex workers are often non-existent in the narrative. Yet, during the women’s movement of the 1970s, the rape narrative began to change. Women started to share their personal stories and experiences, addressing sexual violence at home and in the workplace and Susan Brownmiller’s ground-breaking Against our Will: Men, Women, and Rape (1975) (*6)became the first comprehensive book on rape, changing the traditional narrative.

(*6)became the first comprehensive book on rape, changing the traditional narrative.

It wasn’t until 1994 that the United States passed the Violence Against Women Act (VAMA), and established the Rape Prevention Education Program (RPE). The creation of laws and programs designed to assist survivors of sexual assault as well as fund programs designed to educate and prevent rape and sexual violence made the discussion of rape culture more prominent throughout the United States. Through education at schools and throughout the workplace, RPE funds intervention programs and creates direct prevention efforts (Basile et al., 2007). (*4) Federally funded campaigns such as “No Means No” also worked to bring more public awareness of women’s rights and society’s value of women’s decisions around sex and sexual choices (Lonsway, et al., 1998).

(*4) Federally funded campaigns such as “No Means No” also worked to bring more public awareness of women’s rights and society’s value of women’s decisions around sex and sexual choices (Lonsway, et al., 1998). (*12) All of these laws and policies passed in the 1990s were influenced by the activism of young punk feminists who were making art through zines and defining themselves as riot grrrls.

(*12) All of these laws and policies passed in the 1990s were influenced by the activism of young punk feminists who were making art through zines and defining themselves as riot grrrls.

Paralleling these movements and the rise of feminism throughout the United States came the women’s self-defense movement. Even in the early 1900s, women learned that police were not always willing or ready to protect them from harassment. Women started to discuss that they were more likely to experience violence in the home than from a stranger on the street. Along with the suffrage movement, women practiced self-defense as a way to defend themselves and build self-confidence. Once the first wave of feminism declined in the 1920s, women’s self-defense too was not as prevalent. In the 1960s and 1970s, with the rise of second wave feminism women’s self-defense practices re-emerged. Women started to teach each other self-defense as well as discuss broader issues around sexual assault and sexual violence (Rouse, 2017). (*16) Self-defense in all its forms was a tool of activism and subversion by women and a way to protect against normalization of sexual violence.

(*16) Self-defense in all its forms was a tool of activism and subversion by women and a way to protect against normalization of sexual violence.

As women addressed sexual violence, body politics, and reproductive rights, they took on different forms of feminist activism. Women have a rich history in activism through feminist art, especially as it is used to address social issues, especially those around women’s bodies and women’s rights. bell hooks (2012) (*10) argues that “the function of art is to do more than tell it like it is—it’s to imagine what is possible” (p. 281) and with this feminist art becomes a space to open up discussion around topics and call for social change. Zines are one space in which women have been doing this in subversive ways for decades. In particular, riot grrrl zines, which are both personal and feminist in nature, are important platforms for feminist art as activism.

(*10) argues that “the function of art is to do more than tell it like it is—it’s to imagine what is possible” (p. 281) and with this feminist art becomes a space to open up discussion around topics and call for social change. Zines are one space in which women have been doing this in subversive ways for decades. In particular, riot grrrl zines, which are both personal and feminist in nature, are important platforms for feminist art as activism.

Zines, Zin-ing and Riot Grrrl

Zines, self-publications created for little or no profit, have a long history in radical subcultural spaces. Zines document the histories and narratives not found in most mass-produced texts. Or, if they are, they may be misinterpreted or misrepresented. Many modern zines find their roots in punk subcultures. With access to the photocopier and art school students participating in early punk scenes, the connection between zines, art, and liberal activists was secured in the 1970s. Yet, it wasn’t until riot grrrls that a large group of zinesters started to focus on personal activism and the connection between art, politics, and female control over bodies and choice.

Riot grrrls started to come together in the United States in 1991. As punk feminists,*7 *(7) they were concerned with the double standards in the punk scenes they were participating in at the time. Female punks experienced rape and sexual assault in the scene and needed a space to talk about it. Punk feminists started to form groups, talking with each other about their experiences and encouraging others to do the same. Riot grrrls started using the elements of punk to address the issues within the scene—music and zines—as a way to make others aware of how they were being treated.

Zines became a natural outlet and tool for riot grrrls. Grounded in punk anti-establishment and Do It Yourself (DIY), zines have long been a form of communication in punk spaces. The use of collage, self-promotion, the raw and unedited nature of zines, and the call for everyone to have the equal opportunity to create their scene connected various genres of zines to punks. Zines are weapons to shock and critique culture. They create opposition to mainstream popular cultural texts. And, they do so through the use of art and activism. Zines are tools of art and literacy. Literacy is often looked at as something people know or do not know; being literate or illiterate. But, the New London Group (1996) (*14) argue that we perform literacy in different ways. Literacy becomes something people do as part of their relationships to culture and society. Literacy is social.

(*14) argue that we perform literacy in different ways. Literacy becomes something people do as part of their relationships to culture and society. Literacy is social.

The basic unit of the performance of literacies is what Brian Street defines as a literacy practice, a “behavior and the social and cultural conceptualizations that give meaning to the uses of reading and/or writing.” (p. 2). (*17) They are a way individuals participate in literacy and situate themselves in specific cultural sites. The underground publishing of zines, the counterculture and critique of mainstream media and ideas, the anti-capitalist and anti-copyright elements of zines all contribute to the fundamental ideologies behind zines and zine creation, making zine-ing a literacy practice and the creation of zines a literacy event—when there is a piece of writing that is created as part of the practice (Heath, 1983;

(*17) They are a way individuals participate in literacy and situate themselves in specific cultural sites. The underground publishing of zines, the counterculture and critique of mainstream media and ideas, the anti-capitalist and anti-copyright elements of zines all contribute to the fundamental ideologies behind zines and zine creation, making zine-ing a literacy practice and the creation of zines a literacy event—when there is a piece of writing that is created as part of the practice (Heath, 1983; (*9) Barton and Hamilton, 2000).

(*9) Barton and Hamilton, 2000). (*3) Art is an essential element of the practice and event of zines and zin-ing. The creation of zines follows basic artistic and social beliefs from the communities in which they are created for and by. They are part of the belief in self-publication and alternative presses.

(*3) Art is an essential element of the practice and event of zines and zin-ing. The creation of zines follows basic artistic and social beliefs from the communities in which they are created for and by. They are part of the belief in self-publication and alternative presses.

For riot grrrls, the use of personal narratives and calls for activism became the dominant form of communication and activism in zines. Riot grrrls used personal narratives in their zines, which were used to inform and disrupt traditional cultural and political ideologies. Through cut and paste compilations, riot grrrl activists called for changes to how rape and sexual violence was viewed in their communities and in the larger laws and policies in the United States.

Bringing Everything Together

When riot grrrls started, the United States was declaring that feminism was dead (Bellafante, 1989). (*5) The United States and Great Britain had seen the rise of neoliberalism, brought on by the leadership of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. Tax cuts for the rich, deregulation, privatization, and outsourcing became the norm. The implications of Reagan and Thatcher were seen—and often enforced—across the globe. As the divide between the rich and the poor became larger, the inequality of income and wealth became far more prevalent. Today, the United States is seeing a rise of privatization in public services, education, health care, and prisons. And, through zines and punk ideologies, riot grrrls were at the forefront of the force against the neoliberal agenda.

(*5) The United States and Great Britain had seen the rise of neoliberalism, brought on by the leadership of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. Tax cuts for the rich, deregulation, privatization, and outsourcing became the norm. The implications of Reagan and Thatcher were seen—and often enforced—across the globe. As the divide between the rich and the poor became larger, the inequality of income and wealth became far more prevalent. Today, the United States is seeing a rise of privatization in public services, education, health care, and prisons. And, through zines and punk ideologies, riot grrrls were at the forefront of the force against the neoliberal agenda.

Started by young punk feminists who were active in their punk scenes and tired of seeing women standing in the back of shows or being relegated to being coat hangers,*8 *(8) riot grrrls were more than just a group of women playing in bands. The express purpose of riot grrrl was to create a consciousness raising group where young women had safe spaces to talk about their lives and communities. They seized control of the means of cultural production, creating feminist art scenes through zines. Riot grrrls are often tagged with creating the emergence of third wave feminism, focusing on their personal experiences as a way to challenge the misogyny around them.*9 *(9) Riot grrrl is not necessarily a cohesive group with overarching ideologies or backgrounds, but the use of art activism is seen throughout riot grrrl narratives, especially through the use of zines.

The discussion of sexual assault and violence comes through in some very real ways in riot grrrl zines. The United States’ rape culture normalizes rape and sexual violence, minimizing the experiences of survivors and perpetuating a culture of stigmatism of survivors. In the United States, one in four girls are sexually abused before the age of 18.*10 *(10) Riot grrrls used their zines to share rape narratives, confront their sexual predators, and use punk vernacular as a way to push against the normalized rape myths and rape culture in the United States.

One way riot grrrls used zines was to find other girls to talk with about their experiences. Another way was to gather together and form groups to confront what was happening around them. Through both these practices, riot grrrls brought together punk ideologies and practices of DIY with feminist art activism as a way to challenge and change their communities and social circles. For example, riot grrrl groups formed throughout the country where grrrls would get together, talk about their experiences, and create zines. One important thing that happened during these meetings and through zines was the discussion of self-defense and empowerment. Young women looked for ways to protect themselves from the violence and fear they experience in their everyday lives.

In Olympia, Washington, the riot grrrl group put out at zine about riot grrrls and one of the contributors wrote:

This one night at a riot grrrl meeting some girls started talking about all these rapes that started happening at the college here. We got so mad at the total way the school and the media ignore sexual abuse and harassment. And how shitty it is to live in fear. So we made up a secret plan and carried it out that night. We laughed and held hands and ran around in the dark and we were the ones you should be looking out for. In a girl gang I am the night and I feel I can’t be raped and I feel so fuckin’ free. (No name in Riot Grrrl Olympia’s What is Riot Grrrl Anyway?) (*15)

(*15)

They used their gathering to talk about ways to address the sexual assault and harassment they saw around them. They created their own activist space and then used their zines to share with readers and other participants what they did to combat rape culture around them. In particular, finding ways to work together to protect themselves from the violence and empower themselves, changing their narratives.

They did not only share their experiences, they used their zines as a way to help other women feel empowered. For example, they put together self-defense zines such as FREE TO FIGHT!. (*8) Jody Boyle, the owner of Candy Ass Records, and her bandmates Staci Colter and Anna LoBianco decided to create a record with songs from a number of all-female bands and then create a zine with it as a way to empower grrrls through self-defense, arguing that it was revolutionary. They label it a self-defense/music/art project, writing that “self defense is the equalizer. When a girl defends herself verbally she may feel she is putting herself in a physically threatening position. But when she knows how to fight, she can feel more able to say whatever she wants.” Self-defense becomes self-care.

(*8) Jody Boyle, the owner of Candy Ass Records, and her bandmates Staci Colter and Anna LoBianco decided to create a record with songs from a number of all-female bands and then create a zine with it as a way to empower grrrls through self-defense, arguing that it was revolutionary. They label it a self-defense/music/art project, writing that “self defense is the equalizer. When a girl defends herself verbally she may feel she is putting herself in a physically threatening position. But when she knows how to fight, she can feel more able to say whatever she wants.” Self-defense becomes self-care.

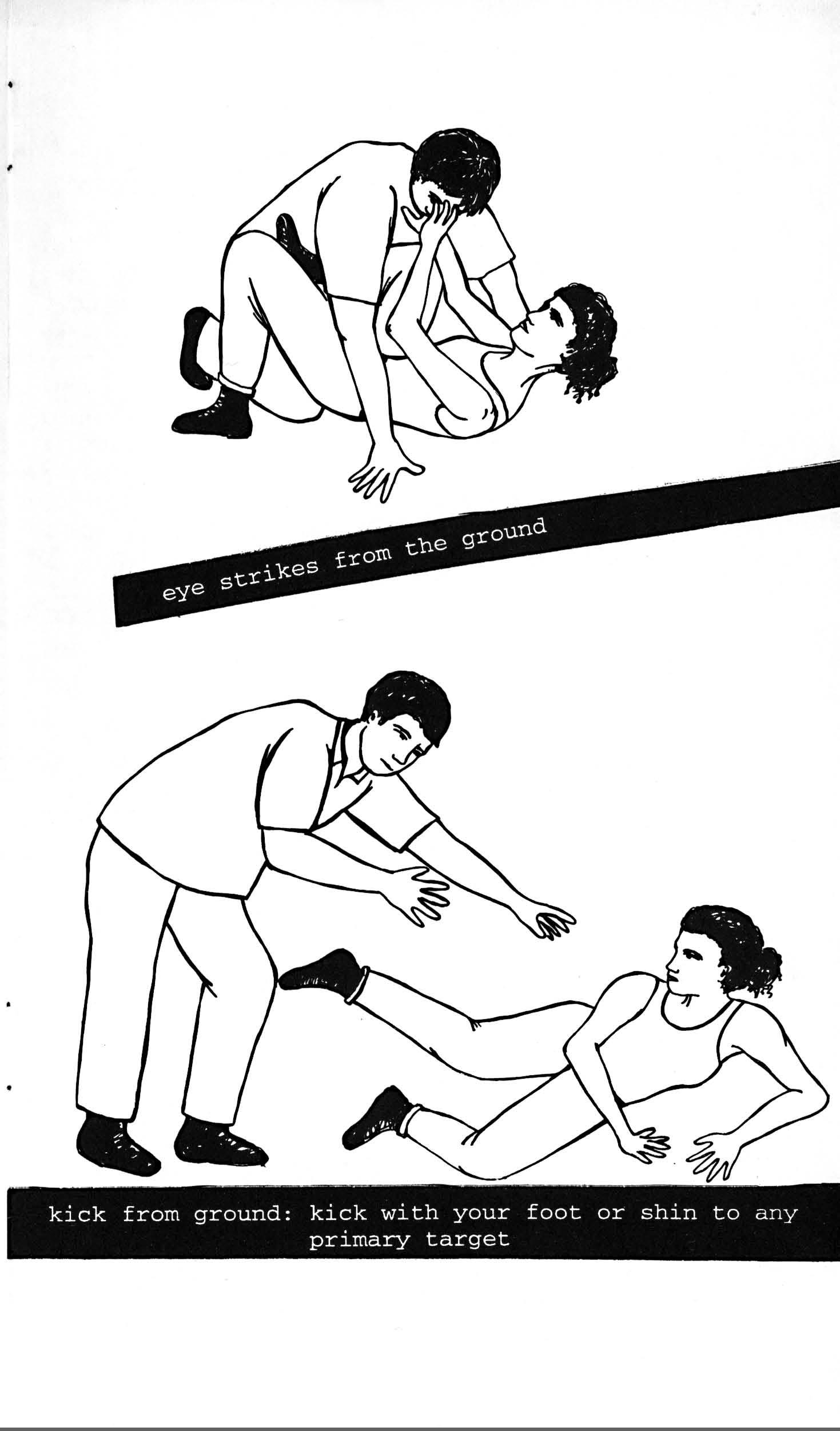

Through a combination of art, cartoon, images, instruction, and personal narrative, the zine becomes a handbook for readers, teaching them tactics such as how to make a fist and suggesting they practice the moves in the zine while listening to the record. They present readers with specifics on how to defend themselves, showing them step-by-step ways in which to make a fist, do an eye strike, or knee someone in the groin. There are images that show the primary targets to stop an attacker (see image #1) or examples of techniques that can be done standing or those that can be used when you are on the ground (see image #2). Interspersed through the record are both songs and specifics on things such as “Definition of self defense,”, “Violence is Violence,” “Body Language” and “Yelling,” Giving readers a way to actively participate as they listen to music is a way to continue to add to DIY and activist spaces through the zine and riot grrrl.

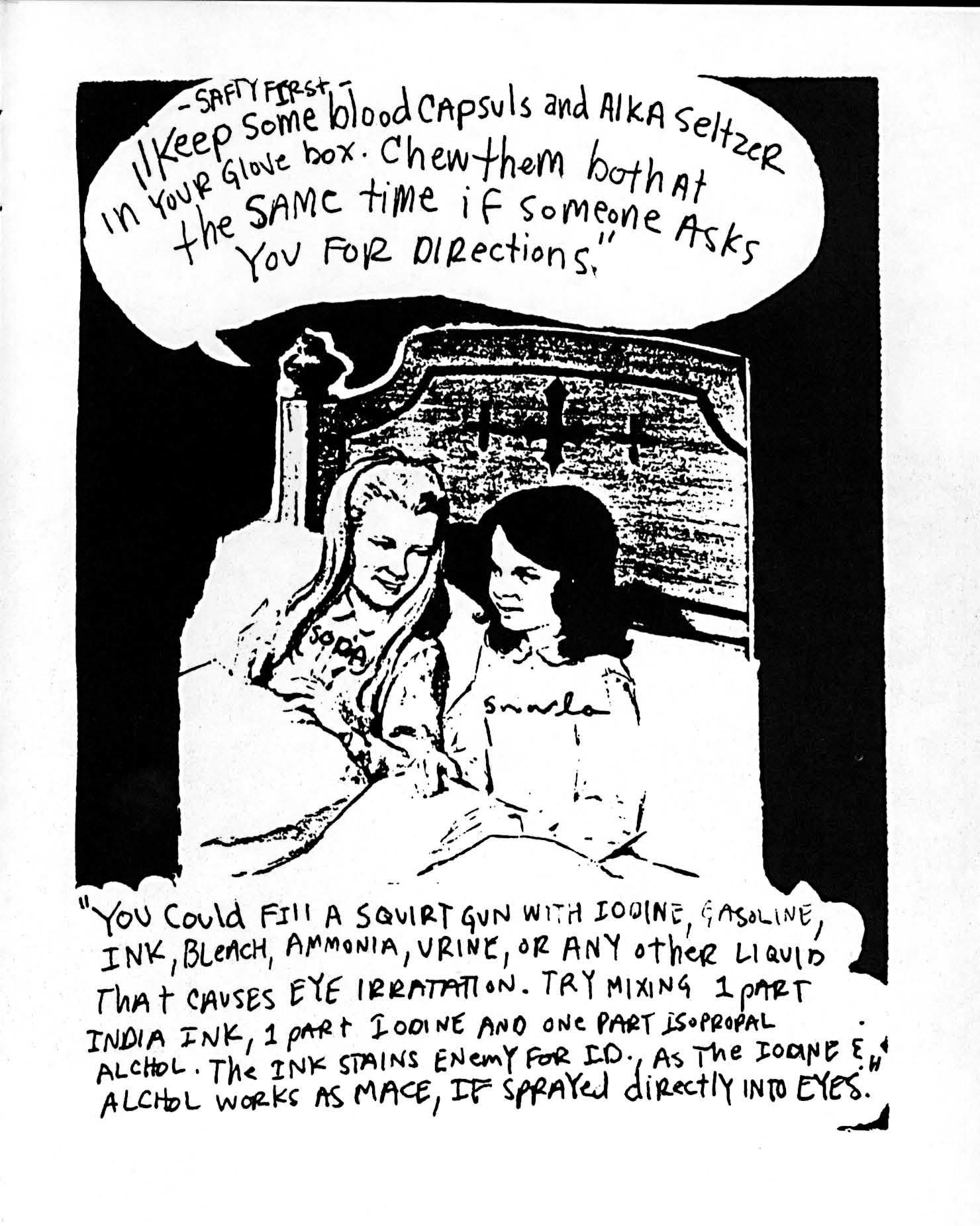

One way that Free to Fight! shows feminist art activism is in the way it presents tools and tips for their readers. Image #3 shows two girls in bed having what looks like a sleep over. The one girl is whispering to the other suggestions for how to be safe if you feel uncomfortable when someone ask you directions—chew Alka Seltzer and blood capsules and the same time and answer their question. The other responds with ways to mix different liquids together to spray at someone’s eyes as an irritant. With the use of image and text as a way to confront assault through art, riot grrrls are creating activist spaces through the formation of their own rhetorics and arts.

The combination of image and narrative as a way to confront sexual violence and educate readers continues throughout FREE TO FIGHT! There are a mix of contributors’ stories both hand-written and typed, facts about sexual assault and rape, definitions of terms that are used throughout the zine and terms they feel are valuable for readers to know, and radical art. Combined, they’ve created an interactive project that called on women’s self-defense projects of second wave feminists, but added punk ideologies and art.

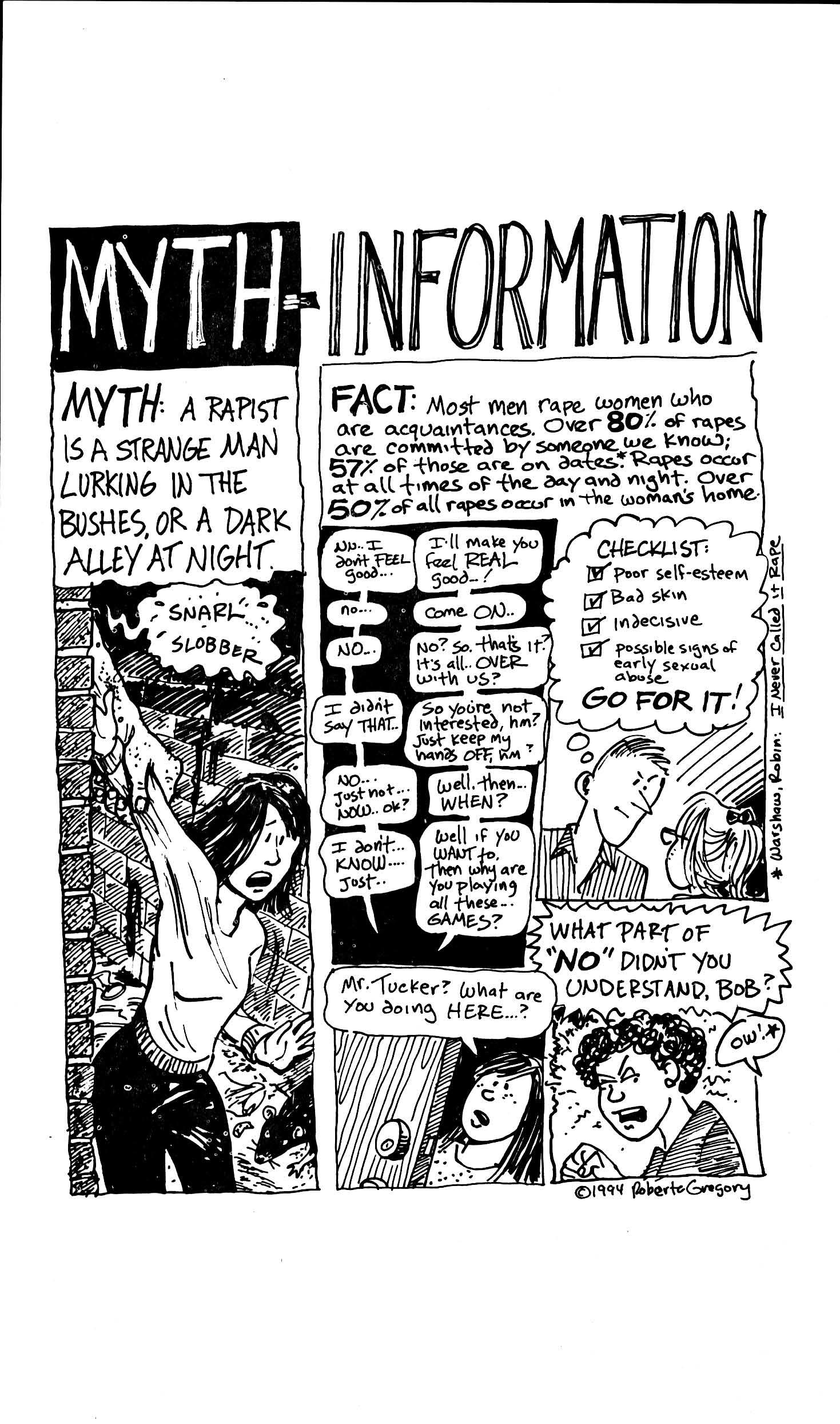

Another example focuses on the use of comics as a way to inform as well as share a narrative. Myth-Information (Image #4) uses graphic images to address the traditional rape myth that perpetuates American culture. Using a long panel on the left to show the dark alleyway that women walk through at night, the artist makes the myth to be a smaller and longer portion of the larger truth. Two-thirds of the page are used to present information. The Fact that most women are raped by individuals they know is presented with four panels, the first with no image and just two rows of word bubbles showing a conversation, the next two showing different ways that men approach who look like younger women who they are attempting to assault and the last with a woman yelling, “what part of NO don’t you understand, Bob?” with the “ow” coming from off the panel, making the reader feel as though Bob has been injured in some way for attempting to assault the women telling him no. This use of comics as a way to inform the reader gives a quick visual that can reinforce the facts that are being presented in the text. Although this information is stated throughout the zine, the comic emphasizes the message of Free to Fight! for the reader and gives imagery behind the facts.

Conclusions

Riot grrrl was a way for young women to take up space in the punk scene. Riot grrrls chose to confront larger social structures that normalized the rape myth through their zines. They created spaces to discuss sexual violence, women’s rights, and body politics. In particular, the use of personal narratives and self-defense and self-help aspects of riot grrrl zines contribute to the larger feminist sites of art as resistance. Riot grrrls paved the way for discussions of the body and the ways in which young women’s bodies are perpetually objectified, commodified, and not allowed to be their own.

Through challenging victim blaming, something we see often today, and reimagining local spaces as safe places for discussion and women’s bodies, riot grrrls were able to create a culture of resistance during the early 1990s. They worked to make a space where young women might not be fearful to live in their bodies without the fear for retribution and abuse. The zines tell a story that is still relevant today, one that we need to listen to, representing feminist activism that uses art to empower and educate.

Anderson, Michelle J. 2005. All-American Rape. St. John’s Law Review: Vol. 79: No. 3, Article 2.

Baehr, Ninia.1990. Abortion Without Apology: A Radical History for the 1900s. Boston: South End Press.

Barton, David, and Mary Hamilton. 2000. „Literacy Practices.“ In Situated Literacies Reading and Writing in Context, by David Barton, Mary Hamilton and Roz Ivanic, 7-15. London: Routledge.

Basile, Kathleen & Chen, Jieru & C Black, Michele & E Saltzman, Linda. 2007. Prevalence and Characteristics of Sexual Violence Victimization Among U.S. Adults, 2001–2003. Violence and Victims. 22. 437-48.

Bellafante, Gina. 1989. „It’s All About Me!“ Time Magazine, June 29.

Brownmiller, Susan. 1975. Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Buchanan, Rebekah. 2018. Writing a Riot: Riot Grrrl Zines and Feminist Rhetorics. New York: Peter Lang.

Candy Ass Records. 1995. FREE TO FIGHT!: An Interactive Self-Defense Project. Portland, OR: Self-published.

Heath, Shirley Brice. 1983. Ways with Words: Language, LIfe, and Work in Communities and Classrooms. London and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

hooks, bell. 2012. Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations. New York: Routledge.

Lai, K.K. Rebecca. 2019. Abortion Bans: 9 States Have Passed Bills to Limit the Procedure This Year. New York Times, May, 29.

Lonsway, K. A., Klaw, E. L., Berg, D. R., Waldo, C. R., Kothari, C., Mazurek, C. J., & Hegeman, K. E. 1998. Beyond „no means no“: Outcomes of an intensive program to train peer facilitators for campus acquaintance rape education. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 13(1), 73-92.

Marcus, Sara. 2010. Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution. New York: Harper Perennial.

New London Group. 1996. A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures. Harvard Educational Review; Spring 1996; 66.1 (60-93).

Riot Grrrl Olympia. nd. “What is riot grrrl anyway???” Olympia: WA, Self-published.

Rouse, Wendy. 2017. Her Own Hero: The Origins of the Women’s Self-Defense Movement. New York: New York University Press.

Street, B. 1995. Social Literacies. Longman: London

This article focuses on zines in the United States. Primarily, it looks at cis-gender women who identify as heterosexual or bisexual and their approaches to issues of sexual assault and violence. The majority of zine writers discussed in this article identify as white. There are many zine writers who identify as queer and other sexual orientations, zine writers of color, and zine writers outside of the United States who also use zines as a form of feminist activism. For my discussion on a wider group of zine writers, see my book, Writing a Riot: Riot Grrrl Zines and Feminist Rhetorics (Peter Lang, 2018).

For an overview of U.S. Rape Shield Law, see the Stop Violence Against Women website (http://www.stopvaw.org), I particular the Evolution of Sexual Assault Criminal Justice Reform (http://www.stopvaw.org/national_sexual_assault_laws_united_states).

Known today as the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice (RCRC), the CCS was formed in 1967 as a response to deaths and injuries through unsafe abortions. The CCS grew to 1,400 members within a year. For more information see the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice website (http://rcrc.org/history/).

Rebekah Buchanan ( 2019): Zines, Art Activism and the Female Body: What We Learn from Riot Grrrls. In: p/art/icipate – Kultur aktiv gestalten # 10 , https://www.p-art-icipate.net/zines-art-activism-and-the-female-body-what-we-learn-from-riot-grrrls/

Artikel drucken

Artikel drucken