Tables and Chairs to Live With

Thoughts on the physicality of education and scholarly work, and its workings in artistic research

As an artist who is interested in educational questions, I have spent quite some time in workshops held in university and academy buildings. Usually, some of this time is spent shifting, pushing, and carrying around tables and chairs. The rooms are filled with these objects. We use them, stack them on top of one another, create the space by arranging them, or we sit at them and write. Nevertheless, these objects and the bodily labor through which we engage with them, often become strangely invisible, providing the background of the workshop scene. Not to mention the unseen labor expended for this scene by caretakers, to provide what then becomes the backdrop for our scene.

The following contemplations are an approach to several questions that have arisen in my artistic practice through the way we engage with everyday objects in educational institutions: How do daily objects in institutions shape our bodies and the ways how we encounter the world and act in it? Moreover, how does paying attention to the physicality of education and scholarly work help in tackling issues of hierarchy and social positioning?

Tables to Think With

Examining the invisibilities of objects that are close to us in institutional education settings, I draw on a text by Sara Ahmed that seems to be full of tables. In “Queer Phenomenology” (2006) (*1) Ahmed uses tables as tools and objects of study in order to philosophically discuss how the individuals’ bodies are oriented towards objects. She investigates how, in relation to certain objects, these “orientations” shape the way we understand the world, what we see and we don’t see. The point that she makes is that philosophy is actually full of tables. They are the objects that philosophy is written upon. However, according to Ahmed, the way they are used or not used in writing requires further scrutiny. Ahmed then starts from the philosopher Edmund Husserl’s obsession with his own writing table that is featured prominently in Husserl’s phenomenological work. In a way it does not seem surprising that tables on which writing takes place appears in writing, because a table “is the object nearest the body of the philosopher” (Ahmed, 2006, p.3).

(*1) Ahmed uses tables as tools and objects of study in order to philosophically discuss how the individuals’ bodies are oriented towards objects. She investigates how, in relation to certain objects, these “orientations” shape the way we understand the world, what we see and we don’t see. The point that she makes is that philosophy is actually full of tables. They are the objects that philosophy is written upon. However, according to Ahmed, the way they are used or not used in writing requires further scrutiny. Ahmed then starts from the philosopher Edmund Husserl’s obsession with his own writing table that is featured prominently in Husserl’s phenomenological work. In a way it does not seem surprising that tables on which writing takes place appears in writing, because a table “is the object nearest the body of the philosopher” (Ahmed, 2006, p.3). (*1)

(*1)

What makes Ahmed’s elaborations appealing here is exactly the nexus that she explores, namely, how an individual’s understanding of the world is entangled with the objects towards which he or she is “oriented” in daily life. The reason for doing this via phenomenology, as the title of the book indicates, is the importance of lived experience, the relationship between consciousness and objects and the significance of repeated and habitual practices in shaping bodies and worlds. One wonders why so little scholarly work, as Ahmed says, actually does pay attention to its direct material working situation. Ahmed herself offers some hints by theorizing “how something becomes given by not being the object of perception” (Ahmed, 2012, p.21). (*2) This can be summarized in the question of how a reality becomes taken for granted; by becoming the background?

(*2) This can be summarized in the question of how a reality becomes taken for granted; by becoming the background?

Approaching these questions, Ahmed is not interested in a “proper” phenomenological method, but instead goes along with the etymology of the word “queer,” which means twisted and off-center, in order to explore how bodies become directed through repetitive practices in relation to objects. Moreover, Ahmed asserts that “bodies as well as objects take shape through being oriented towards each other” (p.54), (*2) meaning that orientation is always a two-way approach. When we touch a table, the table touches us as well. This orientation necessarily shapes our bodies and our world views. What Ahmed introduces here is a relationship of power. Orientation produces exclusions, by turning towards something we also turn away from something else. This orientation makes constituent participants invisible and exercises power, in the way that Husserl, for example, neither included nor theorized the domestic work that made his work at and with his writing table possible. Instead, Ahmed argues, Husserl performed a leap into the universal by replacing “this table” with “the table” (p.35),

(*2) meaning that orientation is always a two-way approach. When we touch a table, the table touches us as well. This orientation necessarily shapes our bodies and our world views. What Ahmed introduces here is a relationship of power. Orientation produces exclusions, by turning towards something we also turn away from something else. This orientation makes constituent participants invisible and exercises power, in the way that Husserl, for example, neither included nor theorized the domestic work that made his work at and with his writing table possible. Instead, Ahmed argues, Husserl performed a leap into the universal by replacing “this table” with “the table” (p.35), (*2) he didn’t recognize that the ones having a place at “the table” are white, male, heterosexual bodies.

(*2) he didn’t recognize that the ones having a place at “the table” are white, male, heterosexual bodies.

Chairs to Practice With

Ahmed’s work on object-body orientations is compelling because she provides entry-points for approaching the physicality of scholarly, educational work and bodily knowledge. The physicality of education has been one of my focuses in the ongoing project “Hidden Curriculum.” The art project “Hidden Curriculum” revolves around the question of how high school students understand, engage with, and ultimately would investigate a so-called hidden curriculum in their specific everyday school environment.*1 *(1) In the context of this project, the term “hidden curriculum” has been understood as everything that is learned in a school context, apart from the official curriculum. During the collaborative research High School students generate small performative situations that comment on and intervene in the routines of everyday school life. One of the trajectories repeatedly chosen by students to pursue, is what I call the physicality of education. By means of performative investigations the students try to describe their spatial settings and body practices. In one of the Hidden Curriculum sessions, a group of students discussed the relations between chair, table, and body in school. “When sitting at a table our legs just fit underneath it. Nobody really pays attention to the space under the desk. That’s really irrelevant. What is important in school are the books, the papers on the table, our hands and head. That’s the way school makes us sit at the table.” What this quote points at is that in everyday experience in school, both the space under the desk and the students’ bodies including their legs go completely unacknowledged. The books or pieces of paper on top of the desk, the hands and head are the main focus of attention. The way the students sit with, and on their chairs at their tables makes invisible a part of the body that seems irrelevant for school processes. What the students portray fits all too well in the preoccupation of schooling with mental processes and can be described as a classical body-mind split. The spatial settings in school emphasize the upper part of the body (especially head, hands), whereas the rest of the body stays unnoticed and hidden under the table. However, especially these parts of the body and the furniture become interesting for the students as examples for an investigation of a hidden curriculum at school. The students investigated the relations between chair, table, and body, and the manifold practices in which the students are engaged with these objects during everyday life in school.

Exercising Chairs, workshop images (Quintin Kynaston School / The Showroom London). Hidden Curriculum / Invisibilities 2012.

In the occupation with small studies on school furniture and trying to redefine its normal usage or functionality, one group of students also looked into how group conversations took place in their lessons and analyzed how they would normally relate to one another spatially and bodily in group discussions in classroom situations. Merging both studies, the group developed the exercise “Collectively Rocking Chairs“.

In this specific response, the students were trying to intervene in classroom routines of learning through other possible ways of engaging in group conversations. The participants hold each other, balancing off the chairs, bodies, and group dynamics of this particular situation while engaging in a group conversation.

Collectively Rocking Chairs, workshop image (St Pauls Way Trust School / Whitechapel Gallery). Hidden Curriculum / In Search of the Missing Lessons 2013

The students re-used a normally individualized practice that is forbidden in school, namely rocking chairs, and introduced it into a collective setting. Bringing a group discussion literally out of balance, the students triggered reflections amongst the participants concerning mutual trust, body language, and questions of hierarchies in discussions held in school. Some of the teachers uttered their disbelief at the exercise and their discontent with allowing rocking chairs, while some students didn’t dare join in because they didn’t have enough trust in each other’s capability of holding each other. However, once the participants engaged in the exercise, it sparked exciting discussions that related to the questions of how we work together, forms of trust, unwritten rules, and the function of our bodies in these relationships. The exercise “Collectively Rocking Chairs” has gained quite some prominence both in school, entering different classroom situations, as well as other workshop settings outside school, such as in a project with the staff of an art organization or at university settings. The exercise has become the departure point for many discussions around hidden levels of complicity between spatial arrangements, bodies, and daily routines of behaving and thinking.

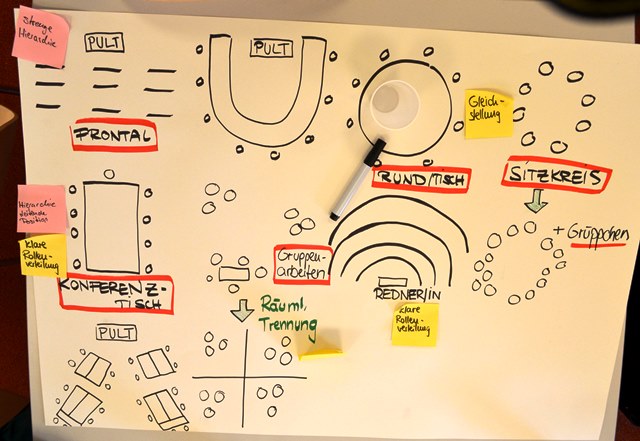

The students’ exercise prompted me as well to do further research into the spatial and bodily arrangement of group conversations and their socio-political implications. One of these arrangements is the so-called roundtable format, which has been one of my preferred discussion arrangements in meetings or workshop settings. In many workshops I was given critical feedback on these considerations, one of these being the workshop “Practices of (Un)learning” in Salzburg in which the participants examined their own classroom routines of learning in their university settings.

Mapping during the workshop “Practices of (Un)learning”. The participants examined their own classroom routines of learning in university settings. In the framework of the symposium “Artistic Interventions and Education as Critical Practice” University of Salzburg 4/5 April 2014).

Round Tables to Discuss with

Drawing on Ahmed’s “tables to think with,” a roundtable is also a working table, but can be only thought of in a collective, often semi-public, constellation, arranged for a group of people. Functioning as working table, a roundtable is often much bigger in scale than a working table for an individual and is used in administrational and educational settings. The term “roundtable” conflates two aspects, which refers to the form of the table and the spatial arrangement, that is, people sitting “a-round” the table. The different spatial constellations that a roundtable demands, consequently also include a change of themes, expectations, and layers of meaning that people bring to the roundtable. In reference to gatherings of individuals in which all are accorded an equal status, the term “roundtable” is most notably a symbol for democratic structures in our times. The democratic expectations and layers of meaning seem to be embodied in the material-spatial arrangements of bodies without necessarily having to postulate these every time anew. Therefore, the symbolic notion of “roundtable” doesn’t remain in a pure linguistic mode, but rather, has to be seen as bodily-structural exercise (see Bourdieu 1977, p. 91 (*3) and Alkemayer, in Krauss 2008, pp.45-64

(*3) and Alkemayer, in Krauss 2008, pp.45-64 (*6)) in democratic behavior every time that individuals perform, e.g., a roundtable discussion. Since all practices are performed in relation to their location, the spatial arrangement of bodies and objects is particularly important in its entanglement with its socio-political implications. In this way, a roundtable discussion must be seen as socio-symbolic-bodily practice. This entanglement is what Bourdieu calls “structural exercises by which is built up practical mastery of the fundamental schemes” (Bourdieu 1977, p. 91).

(*6)) in democratic behavior every time that individuals perform, e.g., a roundtable discussion. Since all practices are performed in relation to their location, the spatial arrangement of bodies and objects is particularly important in its entanglement with its socio-political implications. In this way, a roundtable discussion must be seen as socio-symbolic-bodily practice. This entanglement is what Bourdieu calls “structural exercises by which is built up practical mastery of the fundamental schemes” (Bourdieu 1977, p. 91). (*3)

(*3)

However, further analysis of the circular arrangement of a roundtable can hardly hold its promise of equality. An example from my own experience when I was part of a series of roundtable discussions connected to my work at the Art Academy Utrecht, will indicate some aspects. The first time I was invited to the roundtables I hardly knew anybody. Coming into the room where everybody already was seated, I faced an enclosed circular – roundtable arrangement. Closely seated side by side, it was as if the seated group had collectively turned their back to the outside world. Once I overcame this obstacle and found my place in the circle, I faced another interesting aspect. The circular order renders all participants visible to each other. There is no possibility of placing oneself in the back of the rows, which would give a certain protection if needed – especially for a newcomer, which I was in this setting.

Considering the fact that the circular arrangement supports a greater range of visibility for all actors in the circle, it certainly privileges those who know how to deal with this visibility or who have the power to use the visibility towards their ends.

Roundtable Arrangements and the Paradigm of Visibility

Michel Foucault’s criticism of the dominant paradigm of visibility in Western societies might help to better understand how visibility legitimizes oppressing modes of control in many areas of life, and how this paradigm becomes inscribed in a deeply democratic behavior, such as roundtable discussions exercised in educational or administrational settings like the ones above. In the well-known passages in Discipline and Punish Foucault describes how forms of disciplining are directed at the individual subject in contexts of schools, prisons and hospitals. According to Foucault, the aim has been to optimize the powers of the individual body, specifically its usefulness and adaptation to social structures. In this context, the production of a docile body, a useful body, involves not only direct bodily regulations in the form of punishments; also important are “tiny, everyday, physical mechanisms” that he calls “disciplines” (Foucault, 1977, p.222). (*4) Foucault collects these subtle everyday forces that control and condition the bodies, e.g., in school, such as spatial distribution, in forms of cellular arrangements (classrooms, tables, benches, and chairs) or temporal distributions in the form of rhythms produced, e.g., through time-tables. Through these disciplines, the subject gradually internalizes externally imposed control. Foucault answers the question of the relation between externally imposed control mechanisms and the internalization process with the principle of visibility. This becomes particularly clear in Foucault’s usage of the architectural figure of the panopticon. The panopticon is designed as a circular building with an observation tower at the center of a space that is surrounded by a wall of prisoner cells. The inmates can be seen at any point, whereas the guards in the tower stay invisible. In the words of Foucault, “Disciplinary power is exercised through its invisibility; at the same time it imposes on those whom it subjects, a principle of compulsory visibility” (Foucault, 1977, p. 187).

(*4) Foucault collects these subtle everyday forces that control and condition the bodies, e.g., in school, such as spatial distribution, in forms of cellular arrangements (classrooms, tables, benches, and chairs) or temporal distributions in the form of rhythms produced, e.g., through time-tables. Through these disciplines, the subject gradually internalizes externally imposed control. Foucault answers the question of the relation between externally imposed control mechanisms and the internalization process with the principle of visibility. This becomes particularly clear in Foucault’s usage of the architectural figure of the panopticon. The panopticon is designed as a circular building with an observation tower at the center of a space that is surrounded by a wall of prisoner cells. The inmates can be seen at any point, whereas the guards in the tower stay invisible. In the words of Foucault, “Disciplinary power is exercised through its invisibility; at the same time it imposes on those whom it subjects, a principle of compulsory visibility” (Foucault, 1977, p. 187). (*4) Through the invisibility of the guards, the inmates direct the prison guards’ gaze back at themselves, and submit themselves to the social order of the prison. This mechanism is important because it dis-individualizes and automatizes power structures. Power is no longer found so much in a person as “in a certain concerted distribution of bodies, surfaces, lights, gazes; in an arrangement whose internal mechanisms produce the relation in which individuals are caught up” (Foucault, 1977, p.202).

(*4) Through the invisibility of the guards, the inmates direct the prison guards’ gaze back at themselves, and submit themselves to the social order of the prison. This mechanism is important because it dis-individualizes and automatizes power structures. Power is no longer found so much in a person as “in a certain concerted distribution of bodies, surfaces, lights, gazes; in an arrangement whose internal mechanisms produce the relation in which individuals are caught up” (Foucault, 1977, p.202). (*4) Accordingly, power cannot be solely understood on the basis of domination, as something that is possessed and deployed by individuals. Power is understood as a strategic relation of forces that infuses life and produces new forms of desires, relations, objects, and discourses (Foucault, 1983, p. 212).

(*4) Accordingly, power cannot be solely understood on the basis of domination, as something that is possessed and deployed by individuals. Power is understood as a strategic relation of forces that infuses life and produces new forms of desires, relations, objects, and discourses (Foucault, 1983, p. 212). (*5)

(*5)

Relating this back to the roundtable example, two aspects are important. First of all, it indicates that a spatial arrangement is highly dependent on the socio-political context within which it is placed. It is imbued by the temporal conventions of which it is a part. Following the example I have put forward, I suggest that participating in a roundtable is not only a structural exercise in democratic behavior, but also a structural exercise in the paradigm of visibility that we encounter in contemporary Western societies. The question that arises is how the democratic agency of roundtable discussions is compromised by the current social norms of visibility. Secondly, a different socio-spatial order implies different forms of reproduction of inequality and it would be wrong to think of a “democratic” roundtable as neutral. A roundtable enacts a socio-symbolic-physical order that brings with it new (informal) inclusions and exclusions, which need further considerations and restructuring.

In relation to the “Hidden Curriculum” project, the question of visibility is already present with the project’s title. In discussions it was possible to make use of its somewhat misleading character: “Hidden Curriculum” has been understood that in setting up something that is hidden, it suggests to reveal the invisible. At risk of getting lost here is a closer look at the function of (in)visibilities in society, and the different ways we might relate to them and utilize them for our own agendas. Bringing together thoughts on (in)visibilities (Foucault) and what we take for granted in relation to our orientation towards objects (Ahmed) produces discussions about the extent to which the visible world around us actually remains invisible for us. What I am proposing here is attending to the continuous presence and production of blind spots. And again it might be too easy to primarily think of revealing these blind spots instead of how a blind spot might function in a society in which, for example, the dominant paradigm is one of visibility.

Some Preliminary Conclusions

What brings all the elaborations on power relations together in this text is their refusal to be understood as either discursive or material. Instead, they suggest a material-discursive analysis, which brings to the fore what normally resides in the background: the physicality of education and scholarly work. Moreover, if we follow Foucault again, the subjects in these power relations do not precede their relations, but instead, are produced through these relations. Foucault calls this the concept and paradox of subjectivation: the very processes that enforce a subject’s subordination and correlation to certain norms, are the conditions through which she becomes a self-conscious identity and agent (Foucault, 1983, p.208-225). (*5) Foucault’s understanding of power is important for educational settings and scholarly work, because it neither conceptualizes the students, teachers, and scholars as blank pages for social inscription, nor as omnipotent masters of educational processes or scholarly work. His understanding of power does not reside in either subordination or resistance, but rather, tries to move beyond this binary construction through both subordination and resistance.

(*5) Foucault’s understanding of power is important for educational settings and scholarly work, because it neither conceptualizes the students, teachers, and scholars as blank pages for social inscription, nor as omnipotent masters of educational processes or scholarly work. His understanding of power does not reside in either subordination or resistance, but rather, tries to move beyond this binary construction through both subordination and resistance.

The collaborative research in, e.g., “Hidden Curriculum” touches upon this double approach by investigating the implicit knowledge in practices and objects in school that is hard to grasp as it is hidden by its common, everyday nature. This implicit knowledge is part of everyday life in school and shapes the way we relate to each other and to objects in school. On a more general level, the students’ investigations pose the question as to whether the way we sit on a chair (also in relation to other chairs and object) actually shapes (and restricts) the way we think and how we know these chairs. Through the investigative performances, the students ask not only what a hidden curriculum and the implicit knowledge might mean to them, but just as importantly, they examine what a hidden curriculum does in the realm of the school; how it is produced through our bodies and their material environment; and most importantly, how a hidden curriculum is connected to both processes of subordination and transformation.

Annette Krauss ( 2014): Tables and Chairs to Live With. Thoughts on the physicality of education and scholarly work, and its workings in artistic research. In: p/art/icipate – Kultur aktiv gestalten # 05 , https://www.p-art-icipate.net/tables-and-chairs-to-live-with/

Artikel drucken

Artikel drucken