Peace through Collective Play

Highlighting the Gestural in Undermining Social Striation in the American South

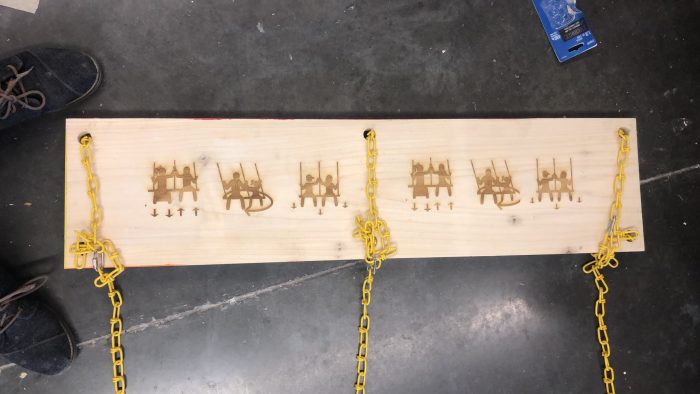

I made two versions of the collaborative swings: individual swings with instructions for co-use (figure D) and a double swing with instructions for use with another individual. The functional/social value of each differed slightly. The single swings, either attached together or separate, were more welcoming in some circumstances, but allowed for individual use; they are perfectly usable without a second participant, although the use of the swings, even separately, functionally re-narrates the space into a play-space, offering a solution for social interconnectedness for both the players and observing parties. Comparatively, the double swings are very difficult to use by individual people involved in play, and require a spatial ask for a second person in order to work. This creates a narrative of need and need filling, which offers an opportunity for help-based collaborative social intersection in order to accomplish play.

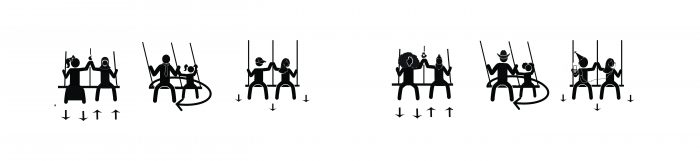

Fig. D: Sample double swing seat and instructional signage, laser-cut into swing.

Initial Trials and Prototyping

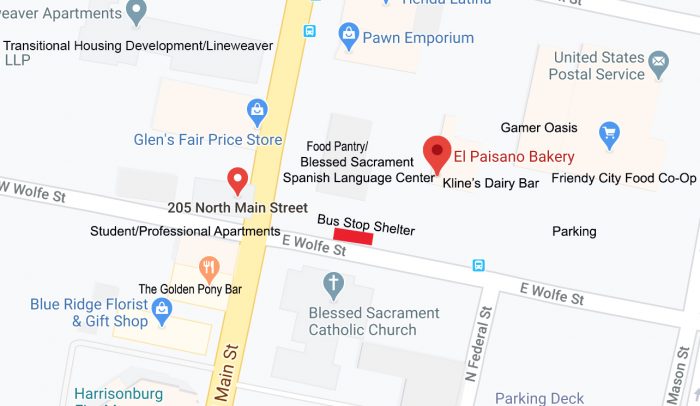

Initial trials of the swing in several identified spaces of social intersection, as described earlier described, initially focused on bus stops, with significant proximity to spaces of need meeting (grocery, clothing supply stores, municipal centers.) and pedestrian and car-based transit spaces. Figure E*1 *(1) shows the makeup of one such space, a bus-stop shelter at what I found to be a significant social boundary. This shelter is in close proximity to a parking lot, which services a Spanish-language market, a bakery, and a specialty ice cream shop that are popular with students and local families, as well as both English-speaking and Spanish-speaking places of worship, an organic, high-end local grocery store, and a food bank. Across the street are transitional apartments for those experiencing homelessness, a student bar, median-income student and professional apartments, and a confederate-flag-emblazoned variety store. This bus stop borders a popular pedestrian area as well as city parking. While an extremely diverse population shares and uses this space, there is limited, if any, social blurring; nearly all interactions between individuals are homogeneous. The swing installation here can be seen in figure E. Notably, this site is not within walking distance of any significant green spaces or parks with play space.

Fig. E: Informal mapping of social-boundary space on Wolfe Street in Harrisonburg, Virginia. Note location of bus shelter.

Early installations along social border sites, such as the one described above, have involved the installation of swings at bus stops. While engaging as objects, limited participation was accomplished for several reasons. The first is that, without a participatory-performative element, individuals were not likely to engage with the swing object absent any indication of weight support and permissible presence. While the swings themselves are all rated to carry 150+ kg, they were installed without municipal permission, and were ultimately removed before significant engagement could be achieved. Additionally, general distrust of the hanging structure limited public willingness to engage with the object.

Fig. F: Bus shelter 931, and El Paisano bakery which is located on Wolfe street in above social-boundary mapping, site for installation shown in Figure F.

Sarah Phillips ( 2020): Peace through Collective Play. Highlighting the Gestural in Undermining Social Striation in the American South. In: p/art/icipate – Kultur aktiv gestalten # 11 , https://www.p-art-icipate.net/peace-through-collective-play/

Artikel drucken

Artikel drucken