Introduction

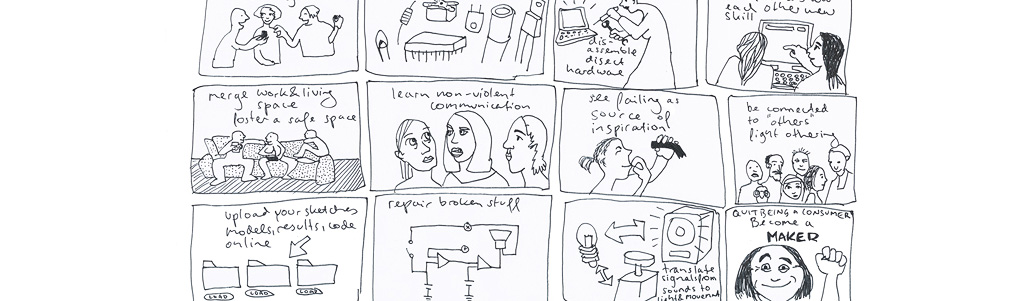

There has been a shift in technology. A shift from the habit of purely consuming technology as a commodity, such as a device, gadget or phone application, towards the trend of wanting to understand, take apart, play with and make technology by yourself. “Do-It-Yourself” (DIY) has become an essential topic in art, design and education. It has brought about new formats of labs that host people working in a hands-on and self-motivated way (Soler, 2008) (* 20 ). The shift from consuming to making things is understood as the core dynamic of the DIY movement. Some groups within this movement aim to generate an alternative production circle, a kind of economy alternative to the mainstream economic system. These groups try to distinguish themselves clearly from makers within the creative industries and other “operators of neo-liberal democracy” (Goriunova, 2008)

(* 20 ). The shift from consuming to making things is understood as the core dynamic of the DIY movement. Some groups within this movement aim to generate an alternative production circle, a kind of economy alternative to the mainstream economic system. These groups try to distinguish themselves clearly from makers within the creative industries and other “operators of neo-liberal democracy” (Goriunova, 2008) (* 9 ). They perceive the opportunity to “do things yourself” as freedom. To them “Freedom also has a dimension of collectivity, collective experience, as it is linked into an understanding of a human being as a social and public being.” (Goriunova 2008)

(* 9 ). They perceive the opportunity to “do things yourself” as freedom. To them “Freedom also has a dimension of collectivity, collective experience, as it is linked into an understanding of a human being as a social and public being.” (Goriunova 2008) (* 9 ) Differently oriented groups, although located on different sides of the political spectrum, are all agents in an emerging field called Open Culture. It includes the creation of new online platforms to collect, distribute, network, archive artifacts produced with DIY tools. “The current change, in one sentence, is this; most of the barriers to group action have collapsed, and without those barriers, we are free to explore new ways of gathering together and getting things done. (Shirky 2008: 22)

(* 9 ) Differently oriented groups, although located on different sides of the political spectrum, are all agents in an emerging field called Open Culture. It includes the creation of new online platforms to collect, distribute, network, archive artifacts produced with DIY tools. “The current change, in one sentence, is this; most of the barriers to group action have collapsed, and without those barriers, we are free to explore new ways of gathering together and getting things done. (Shirky 2008: 22) (* 19 ). The reader can get an impression of which kind of projects are produced and shared if one visits the web platform “thingiverse” [www.thingiverse.com]. This dynamic website hosted by Maker Bot offers users to add to and download from a database of projects related to DIY 3D print. Or you could explore the website processing.org, that collects projects realized with the DIY graphic environment Processing for creating images, animations, and interactions. These self-made pieces of software and artifacts are licensed as “creative commons” (CC). This licence allows users to re-use, adapt, basically change the existing materials on every level, without having to pay the author or ask for permission as the default “all rights reserved” would suggest. The user might need to give credit to the author and e.g. label it as running under “creative commons”, making it into a “some rights reserved” license. However, if a work is labeled as CC (creative commons license) the public receives permission to access it. This means that enthusiastic makers worldwide are free to mix and use materials published under CC for their purposes. Fabrics, old toys, electronic elements, code and even integrated circuits turn into potential things to tinker with. It might be the sensual feeling of soldering, the reward of being able to construct something with your own hands or the individual self expression achieved with the DIY-spirit that draws so many people into this movement. Yet the practice of using random materials or integrated circuits for self-made projects has reached a turning point. Companies have started to take advantage of DIY’s inherent drive. The publisher O’Reilly has presented more than five books on “Making Things” in Europe only in the last three years (Make: Electronics 2010, Making Things Move 2011, Making Things Talk 2012, Making Things Wearable 2012). For companies and entrepreneurs DIY smells like big business. Another critical point in the movement is the fact that being a “maker” has become synonymous for tinkering in DIY manner with electronics and tech-related materials. Becoming a “Maker” and being a “Maker” sounds like something open to everybody, but it actually comes with quite a few requirements. Although the web provides users with instructions and tutorials on how to make things on countless online platforms, the actual making of things demands awareness and a set of skills, something that is usually not mentioned by the experts providing support. It needs trust in ones own potentials and access to tools and machines. The phrase “Do-It-Yourself” has recently transformed into “Do-It-Together”. This is not because the collaborative aspect in tinkering is held in such high priority in the movement, but rather that the term “Do-It-Together” originates in the necessity of working in groups in order to reach the desired results. As soon as cutting-edge technology is involved, sharing tools, equipment and experiences is essential for a successful outcome. Moreover, the ability to formulate a tech-related question in a comprehensive way as well as in the lingua franca, English, is increasingly important. Only this way a person to who you are only connected via internet will be able to help you out. When you are stuck with a problem, being affiliated to one of their communities is unavoidable. In his paper “On free software art, design, communities and committees” Dave Griffiths claims:

(* 19 ). The reader can get an impression of which kind of projects are produced and shared if one visits the web platform “thingiverse” [www.thingiverse.com]. This dynamic website hosted by Maker Bot offers users to add to and download from a database of projects related to DIY 3D print. Or you could explore the website processing.org, that collects projects realized with the DIY graphic environment Processing for creating images, animations, and interactions. These self-made pieces of software and artifacts are licensed as “creative commons” (CC). This licence allows users to re-use, adapt, basically change the existing materials on every level, without having to pay the author or ask for permission as the default “all rights reserved” would suggest. The user might need to give credit to the author and e.g. label it as running under “creative commons”, making it into a “some rights reserved” license. However, if a work is labeled as CC (creative commons license) the public receives permission to access it. This means that enthusiastic makers worldwide are free to mix and use materials published under CC for their purposes. Fabrics, old toys, electronic elements, code and even integrated circuits turn into potential things to tinker with. It might be the sensual feeling of soldering, the reward of being able to construct something with your own hands or the individual self expression achieved with the DIY-spirit that draws so many people into this movement. Yet the practice of using random materials or integrated circuits for self-made projects has reached a turning point. Companies have started to take advantage of DIY’s inherent drive. The publisher O’Reilly has presented more than five books on “Making Things” in Europe only in the last three years (Make: Electronics 2010, Making Things Move 2011, Making Things Talk 2012, Making Things Wearable 2012). For companies and entrepreneurs DIY smells like big business. Another critical point in the movement is the fact that being a “maker” has become synonymous for tinkering in DIY manner with electronics and tech-related materials. Becoming a “Maker” and being a “Maker” sounds like something open to everybody, but it actually comes with quite a few requirements. Although the web provides users with instructions and tutorials on how to make things on countless online platforms, the actual making of things demands awareness and a set of skills, something that is usually not mentioned by the experts providing support. It needs trust in ones own potentials and access to tools and machines. The phrase “Do-It-Yourself” has recently transformed into “Do-It-Together”. This is not because the collaborative aspect in tinkering is held in such high priority in the movement, but rather that the term “Do-It-Together” originates in the necessity of working in groups in order to reach the desired results. As soon as cutting-edge technology is involved, sharing tools, equipment and experiences is essential for a successful outcome. Moreover, the ability to formulate a tech-related question in a comprehensive way as well as in the lingua franca, English, is increasingly important. Only this way a person to who you are only connected via internet will be able to help you out. When you are stuck with a problem, being affiliated to one of their communities is unavoidable. In his paper “On free software art, design, communities and committees” Dave Griffiths claims:

Software with a good community surrounding it is more useful than software which is engineered well, but lacks a community. Engineering alone is not enough to get most people’s attention or continued interest, and doesn’t guarantee people investing time learning and using it. It’s a mistake to separate the executable product from it`s community when discussing software. The community dictates the future of software.

The same counts for communities evolving around free hardware, such as the Arduino Microcontroller board or Open Culture practices as “Crafting”, a form of activism pushed forward by groups like the critical crafting circle (Gaugele, Kuni, 2011) (* 8 ). The new context of DIY tinkering in combination with a strong feeling of community and belonging to a platform allowed new group identities to emerge. Groups for mutual support, but as well for a mutual social experience. 3D print, Pure Data, V4, Raspberry Pi, SuperCollider are just a few tools that attract and connect a powerful network of users and developers. Many of these supporter groups articulated the need for a physical space to meet as real people, not as users only. A place that offers the chance of failure while in a safe space and a physical environment for experiments while members are passionately trying something new for the first time. Regular meetings and festivals were established to enable real world encounters and foster collective exploration. (For example the Piksel Festival in Bergen, that was born out of the collaboration of an artist and a programmer, Gisle Froysland and Carlo Prelz (Oreggia, 2008

(* 8 ). The new context of DIY tinkering in combination with a strong feeling of community and belonging to a platform allowed new group identities to emerge. Groups for mutual support, but as well for a mutual social experience. 3D print, Pure Data, V4, Raspberry Pi, SuperCollider are just a few tools that attract and connect a powerful network of users and developers. Many of these supporter groups articulated the need for a physical space to meet as real people, not as users only. A place that offers the chance of failure while in a safe space and a physical environment for experiments while members are passionately trying something new for the first time. Regular meetings and festivals were established to enable real world encounters and foster collective exploration. (For example the Piksel Festival in Bergen, that was born out of the collaboration of an artist and a programmer, Gisle Froysland and Carlo Prelz (Oreggia, 2008 (* 15 ))).

(* 15 ))).

In this article I want to focus on female makers in this quite peculiar DIY movement. Although they feel related to the maker community described above, female makers are still a minority within the movement. To illustrate how this group of people is working, I want to focus on a feminist Hackerspace that I am part of myself: Miss Baltazar’s Laboratory.

Stefanie Wuschitz ( 2013): Female Makers. In: p/art/icipate – Kultur aktiv gestalten # 02 , https://www.p-art-icipate.net/female-makers/

Artikel drucken

Artikel drucken