Feminist Hackerspaces

A hackerspace is a specific type of maker lab, dedicated to hacking, which is understood as the use of technology in a different way than intended by its developer. For example, to use your ashtray as a flowerpot is kind of hacking an ashtray. The feminist hackerspace I am member of, was founded in Vienna in 2009 by a group of female makers in a male dominated hackerspace. The group called itself Miss Baltazar’s Laboratory (MBL). It later became a self-managed autonomous lab in a different location than the original hackerspace in which it started. MBL focuses on giving participants access to new technologies through workshops. All workshops are organized by women and trans for women and trans. While being part of the developing process, I made observations in other international feminist tech groups: MzTek (London) and Genderchangers (Rotterdam). Both are inviting environments that can supply members with the tools required to tinker, hack and make things. A network that allows you to fail, but encourages you to try again with even more persistence. Not intimidated by gender scripts, participants can explore new concepts and techniques. In this text I want to explore why this development came about and raise the question of how a lab’s culture can grow more inclusive.

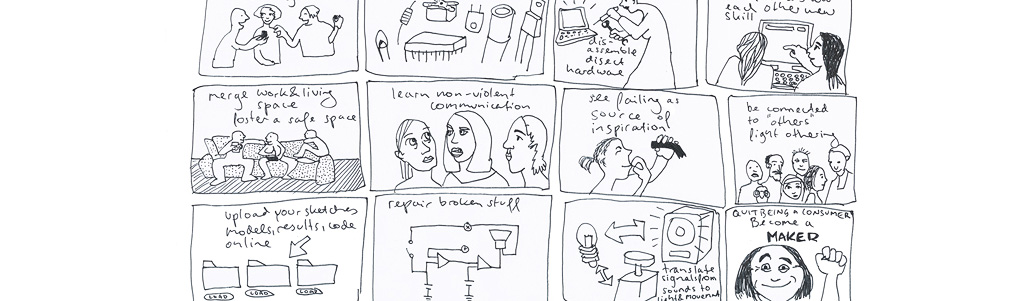

Miss Baltazar’s Laboratory Workshop at a hackerspace at Treasure Hill Artist Village, Tapai, Taiwan 2012

Hackerspaces and Open Source

The maker community is strongly affiliated with the Open Source Community (FLOSS+Art 2008). Also female makers often use Open Source Software to realize their projects. The advantages are manifold. First of all: accessibility online, then of course the open license that allows users to download and change the given code or material in the process of production. Finally most agents in the maker community want to point to the absurd relation between need and capital in the cooperative world. Through the example of Open Source Software they hope to demonstrate how easy it could be to explore different economic systems. Inspired by algorithmic production that creates endless replications of graphic objects through code, members of the maker community invented a 3D printer that can, for a low price, produce identical objects from digital 3D models. People are envisioning to create spare parts to fix broken machines, print out items they need or do not want to purchase. This project is a collaborative effort, well documented on websites as e.g. thingiverse.com mentioned above. This quite idealistic Open Source Hardware project has lead to a similar buzz in the community as e.g. to the ambitious project of the Ubuntu operating system, which today is seen as a successful threat to the Microsoft monopoly. Some speak of a paradigm change. Yet many projects spinning off the maker community, and this counts for the 3D printer as well, end in commercial applications, far off the spirit of the Open Source movement of the earlier days.

Some agents decided to re-invent and merge different fields of production within the same local physical space, then hackerspaces and Open Labs came into existence. They basically serve as working and production spaces and offer second living rooms for the agile community. Within this environment everything required for the product-circle is available, the original Open Source spirit is worshiped. The hackerspace is a small factory: from scratching the first idea, developing a concept and making a machine to realize the product, up to the distribution of not only the product, but the plans and instructions for the machine as well – be it an online application or a digital tool –, much is documented and published. While the products are still the expected end-results, the main attention is spent on the machine that is meant to create the desired output or product. This flip of intention (to be more interested in inventing tools of production rather than generating the product itself) can be interpreted as a trend towards makers wanting to keep control over all sections of the production-circle. Usually the way each section of the production circle is being built will be open and made accessible to others. The aim is to support each other in the development of independent off-scene ideas. Hence the makers explore ways of sharing their experience through online tools and digital media. Speaking of my own experiences in these environments, I must confess that I believe that what we learn changes us . The newly acquired skill is integrated in the self. For example a new habit or an identity narration telling me “I’m someone who can do this”, “This is what I can do”. The process of being part of entire sections within the production circle has got the potential of de-constructing long-held determinisms. Most hackerspaces are run by participants who feel close to the technology scene and IT sector. What distinguishes the Open Source Community from profit-orientated associations is their focus on social aspects like e.g. as a group aiming for equality. Yet, the community is not separated from mainstream culture and deeply interwoven with old power structures. Participants in Open Labs and hackerspaces struggle hard to get awareness and work on the dynamics that grant equal value to persons in their own community. Emerging hierarchies and power structures need to be evaluated and de-constructed again and again (Galloway 2004) (* 7 ). Often the Open Space Community shares the opinion that personal commitment is an individual decision rather than a consequence of working/living conditions outside a certain space. Therefore, participants who spend more time in the lab are seen as legitimately more influential. However, time and resources someone can invest into a shared space are dependent on conditions outside the lab. Free time is a precious resource mostly enabled through a stable income. A stable income mostly depends on education and position. But it also strongly depends on gender. The Gender Pay Gap in Germany was 23% in the year 2010 (Destatis, 2013)

(* 7 ). Often the Open Space Community shares the opinion that personal commitment is an individual decision rather than a consequence of working/living conditions outside a certain space. Therefore, participants who spend more time in the lab are seen as legitimately more influential. However, time and resources someone can invest into a shared space are dependent on conditions outside the lab. Free time is a precious resource mostly enabled through a stable income. A stable income mostly depends on education and position. But it also strongly depends on gender. The Gender Pay Gap in Germany was 23% in the year 2010 (Destatis, 2013) (* 5 ). Due to lower income, female makers tend to sacrifice less time and budget on Open Labs or into Open Source projects. Thus, feeling comfortable in a space is widely perceived as a question of personal taste or sympathy rather than a question of dominance. A group of men who spends a lot of time in an Open Lab can mark territory by gestures and male habitus, resulting in reduced comfort and diversity in a lab. If such problems get individualized rather than fought against as a communal issue that mutually affects all participants, the lab is not inviting to others. This leads to a form of bias, but most of all to a gender gap. In the hackerspaces I was researching, only one half to five percent of all members were females.

(* 5 ). Due to lower income, female makers tend to sacrifice less time and budget on Open Labs or into Open Source projects. Thus, feeling comfortable in a space is widely perceived as a question of personal taste or sympathy rather than a question of dominance. A group of men who spends a lot of time in an Open Lab can mark territory by gestures and male habitus, resulting in reduced comfort and diversity in a lab. If such problems get individualized rather than fought against as a communal issue that mutually affects all participants, the lab is not inviting to others. This leads to a form of bias, but most of all to a gender gap. In the hackerspaces I was researching, only one half to five percent of all members were females.

Stefanie Wuschitz ( 2013): Female Makers. In: p/art/icipate – Kultur aktiv gestalten # 02 , https://www.p-art-icipate.net/female-makers/

Artikel drucken

Artikel drucken